An interview with Stan Mack

“You don’t have to be Jewish to enjoy Levy’s Rye Bread,” was a very successful ad in New York City some years back. And the same holds true for Stan Mack’s remarkable accounting of, as he puts it, The Story of the Jews, a 4000-year Adventure, a graphic novel that doubles as a textbook of one of the world’s oldest religions.

He was right up front with me when he told us that he’s “not a cartoonist by the usual definition. It’s really a closer relationship to newspaper reporting.”

He was right up front with me when he told us that he’s “not a cartoonist by the usual definition. It’s really a closer relationship to newspaper reporting.”

On the other hand, in recent times there’s been, “a burst of non-fiction reporting within the graphic novel form,” a description that also includes my Father’s Day gift from my daughter, Stan Mack’s Taxes, the Tea Party and Those Revolting Rebels, A History in Comics of the American Revolution, a delightful graphic record endorsed by teachers from schools in Chicago, New York and Harvard as “scholarly yet accessible – also great fun. Every kid should have it.” (Stanley Brimberg, The Bank Street School, New York City.)

Stan Mack never planned to be a cartoonist, “so the subject [of a career] never came up with my parents. Certainly they saw no future in my doodling.”

However, it was a teacher, Ms. ‘Red’ Johnson in Social Studies at Nathan Bishop Junior H.S. in Providence, RI, who sort of got him going. “She encouraged me,” he reveals, “to draw political cartoons for her ancient history assignments.”

I was delighted when Stan said that two artists in particular intrigued him as he was growing up. They were Milt Caniff (“Terry and the Pirates” and “Steve Canyon”) and Willard Mullin, sports cartoonist/workhorse of the New York World Telegram, both of whom graciously gave me samples of their work long before my debut in the Humor Times. He loved the way Caniff made brilliant use of shadows, while Mullin “was a genius with his drawing the body in action. Both artists work stands up at least as well today as it was in their time.”

It’s hard to avoid bring up the internet as a subject in today’s cartooning world. Mack says, “The Internet is just the latest version of cave painting, except today’s cave art shows up on thousands of caves at the same time. Technology changes and our view of the world and universe changes. Cartoonists adapt, but after all is said and done, cartooning doesn’t change.”

Stan Mack is an artist with many stories to tell. He recently released an illustrated memoir, “Janet and Me,” a touching story of his 18-year relationship with “Janet Bode, a lighthearted fling that beat the odds to become an enduring love affair. The only thing they couldn’t beat was cancer,” and according to Simon and Schuster, who published this remarkable work, it is “a beautifully told love story, for anyone who is touched by someone suffering from serious illness and looking for practical guidance and for anyone who appreciates a life lived to the fullest.”

From his own vantage point, he tells young artists to “pursue the dream until the fire dies out. Meanwhile expect the unexpected.” He surprised me when I asked him what his friends and teachers would say about him now; his unexpected reply was, “…not much. Most are either dead or can no longer remember!”

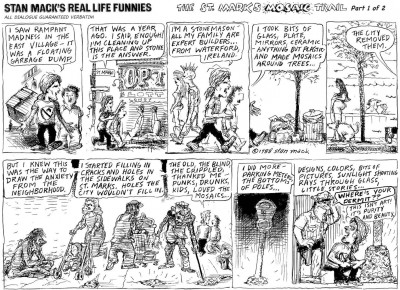

Mack, whose “Stan Mack’s Real Life Funnies,” ran in the Village Voice for over 20 years, says he gets his inspiration from people he meets and his work for the Voice was noteworthy for its semi-documentary feel. Wikipedia tells us: “All dialog was culled from Mack’s observations, and reported as 100% Guaranteed Overheard. He said of it that this job gave him an excuse to accost people, to be pushy and aggressive.” He goes to say he could take notes on his shirt cuffs and walk backwards in crowds, but most of all he learned to listen to other people.

Speaking of other people, if given the chance, Stan would love to meet with Honore Daumier, the great French “Michelangelo of caricature,” to discuss, of course, his critically acclaimed, hardly-flattering drawings of his contemporaries. The visual satirists of the past are all of interest to him, as he tells us that should he be on that long journey to outer space (or even confined in a snowstorm to a mountain cabin), he’d love books on Hogarth, Dore, Goya. And he hopes they would be “written by journalists and have lots of pictures.”

This year’s horrible attack in Paris on the writers for the satiric magazine Charlie Hebdo brought us to the whole subject of freedom of the press and censorship. Stan Mack tells us, “I ran into an unexpected kind of censorship over my comic strip in the Village Voice in which I secretly joined the training for Macy’s Christmas elves. When my story came out, Macy’s angrily complained to the paper’s Business Department who complained to my editor who then lectured me. Apparently there was no problem having complete freedom to report on the training of elves so long as no one criticized the guy in charge.”

Nearing the end of our interview, I wanted to know into whose skin he’d jump if he had the chance. “Everybody, for an hour each!” he said. And what changes could he make if he could do it all over again? “Wise up sooner,” he replied.

When I mentioned to him that I do all my preliminary writing on a vintage portable typewriter, he was tickled. “You write on a 1936 Underwood? Wow. Could the typewriter maker of those days even have imagined pixilated data?”

And his last words to assembled friends and family some decades down the line: “Does anyone know where the nearest bathroom is?”

You can, as occasionally happens, mock my words, but this time you can mark them! Stan’s the Man, Mack no mistake about that!

- Insight on Cartoonists: Michael Capozzola - March 2, 2016

- Insight on Cartoonists: Signe Wilkinson - February 12, 2016

- Insight on Cartoonists: Terry Mosher - January 3, 2016