We know the Joker. We’ve seen him nearly constantly.

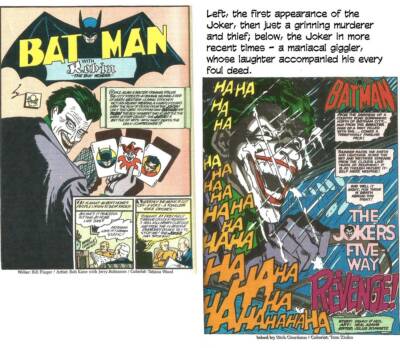

We know the Joker. We’ve seen him nearly constantly. He is, without doubt, the best-loved, most despised of the villains in comicbooks. We also know he’s nuts. He laughs as he commits crimes, grins without mirth, his face the grinning rictus of death, and he murders people in fiendish ways. Who laughs as he kills? Only a nutcase like the Joker.

And he almost didn’t have an encore. In Robinson’s original script, the Joker dies, plunging to his death when Batman knocks him off a building. But DC’s editor Whitney Ellsworth realized that the character was good enough for many encores and recommended that the Joker survive his fall. And he did. With a vengeance.

And he almost didn’t have an encore. In Robinson’s original script, the Joker dies, plunging to his death when Batman knocks him off a building. But DC’s editor Whitney Ellsworth realized that the character was good enough for many encores and recommended that the Joker survive his fall. And he did. With a vengeance.

The crazed character who laughs as he kills quickly inspired stories that were laminated with his inexplicable jocularity. And an endless parade of writers and artists have tirelessly explored the maniacal character for whatever new surprised shock it is capable of provoking. The Joker is inexhaustible in that respect: he cannot be easily explained, so endless explanations are possible.

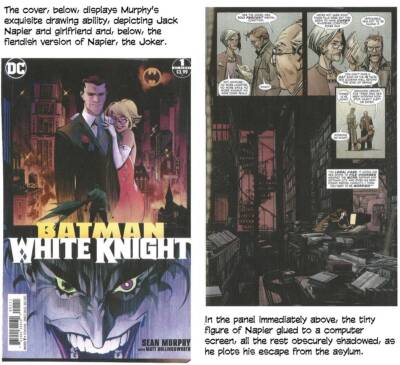

Writer/artist Sean Murphy tried a new explanation a couple years ago in Batman: White Knight, wherein the Joker is half of a split personality, Jack Napier being the other. And as Napier, the Joker quickly emerged as the Good Guy in the 8-issue series. But he relapsed often. And finally.

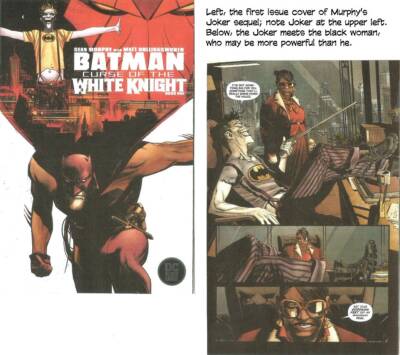

But Murphy is back with more in the same vein in Batman: Curse of the White Knight.

But Murphy is back with more in the same vein in Batman: Curse of the White Knight.

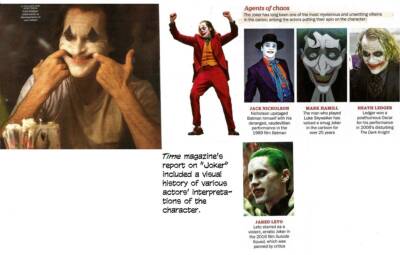

Murphy’s Joker is a four-color fiction albeit on slick paper; and on the big screen yet another Joker has returned in just “Joker,” a movie in which the beloved crazed villain is the central character. I haven’t seen the movie (yet), but the critics are wildly enthusiastic about it, already anticipating an Oscar for Joaquin Phoenix, who plays the fiendish giggler. And the movie has crossed the $1 billion mark at the global box office, Scoop reports—“making it the first R-rated movie in history to reach such a milestone. Impressively, ‘Joker’s’ success also comes without the help of the Chinese market.”

IN THE MOVIE, the life of the titular character aka Arthur Fleck, is traced from his youth (he still lives with his mother whom he loves/hates) through his present unrewarding employment as a clown. Nothing ever goes right for him. Distressed by all of this mundaneness and abuse, he simply goes mad and turns into a psychopathic killer, the extremity of which behavior is wholly unexplained by what we’ve seen previously on the screen. (Or so I assume without having seen it.)

To Anthony Lane in The New Yorker (October 7), the most compelling thing about the movie is “the prowess with which [its star] Joaquin Phoenix holds it all together. His face may get the greasepaint, but it’s his whole body, coiled upon itself like a spring of flesh, from which the movie’s energy is released. He’s so thin that, when he strips to the waist and bends, his spine and shoulder blades jut out from the skin; is he a fallen angel, with his wings chopped off, or a skeleton-in-waiting, halfway to the grave? …

“The trouble is that [director Todd] Phillips, too, is in thrall to his hero, unable to avert his gaze, or his camera, from the lurid spectacle. …

“‘Joker’ peaks in chaos and conflagration, ignited by Arthur’s crimes … The city swarms with a mob of the frustrated, all sporting Joker masks and wreaking indiscriminate revenge. Arthur smiles indulgently upon them, like a wolf surveying its pups, then climbs onto the hood of a smashed vehicle and glories in the applause.”

Lane is reminded of 1949’s “White Heat” in which James Cagney goes up in flames at the movie’s end, maniacally “laughing his way to perdition.”

In Time (October 7), critic Stephanie Zacharek understands that “the Joker is one of the best-loved villains among fans of comicbooks and comicbook movies, maybe because moody teenagers gravitate toward the ‘laughing on the outside, crying on the inside’ clown aesthetic.”

The violence the Joker commits (of the “See what you made me do?” sort) “makes him feel more in control. Killing empowers him.

“As a character, the Joker appeals deeply to the human tendency toward self-pity,” Zacharek says, “and Phoenix’s performance leans hard on that. Skills on display include but are not limited to leering; jeering; air-horn-style blasts of laughter timed for maximum audience discomfort; funky-chicken-style dance moves; the occasional blank, dead stare; and assorted moony expressions indicating soulful lonerism. He hops around like an unhinged Emmett Kelly, twisting his physique into weird, unsettling shapes. His body has a rubbery angularity, like a poultry bone soaked in Coca-Cola. You could call it great acting; it’s certainly a lot of acting. But instead of inspiring compassion, Phoenix wrings it out of us. He’s a wonderful actor, but this material brings out the showiest in him, not the best.”

Zacharek goes on: “Arthur is a mess, but we’re also supposed to think he’s a kind of great, a misunderstood savant. … He inspires chaos and anarchy—in addition to being a murderer, plain and simple—but the movie makes it look like he’s starting a revolution where the rich are taken down, the poor get everything they need and deserve, and the sad guys who can’t get a date become heroes. Is he a villain or a spokesperson for the downtrodden? The movie wants it both ways. Its doublespeak feels dishonest.”

Zacharek goes on: “Arthur is a mess, but we’re also supposed to think he’s a kind of great, a misunderstood savant. … He inspires chaos and anarchy—in addition to being a murderer, plain and simple—but the movie makes it look like he’s starting a revolution where the rich are taken down, the poor get everything they need and deserve, and the sad guys who can’t get a date become heroes. Is he a villain or a spokesperson for the downtrodden? The movie wants it both ways. Its doublespeak feels dishonest.”

At nytimes.com, Lawrence Ware said: “What struck me most is that what the film wants to say — about mental illness or class divisions in American society — is not as interesting as what it accidentally says about whiteness. For it is essentially a depiction of what happens when white supremacy is left unchecked. It shows the delusions that many white men have about their place in society and the brutality that can result when that place is denied.”

And Sonny Bunch at washingtonpost.com calls “Joker” “one of the more fascinating documents of our time.” He continues: “Warner Bros has spent $60 million making, and God only knows how much marketing, a movie in which Antifa kills Thomas Wayne and, we presume, creates the Batman. It’s no wonder the provocateurs at Venice rewarded the film and its director, Todd Phillips, with the Golden Lion, while the stiffs at TIFF sniffed. … Phoenix portrays the Joker as an agent of chaos — alternately dancing with nimble grace and running from cops with a sort of slapstick shamble; laughing uncontrollably as a rictus of sadness animates his face — and as such, he’s no architect of destruction. Rather, he’s simply a flashpoint.”

IN DENVER where I live, a movie theater in the Aurora suburb declined to show “Joker.” It was the theater in which a dozen people died and more than 70 were injured on the night of July 20, 2012 during a murderous rampage at the midnight screening of “The Dark Knight Rises.” The shooter, like Arthur Fleck, was a socially isolated person who felt “wronged” by society. He also dyed his hair orange in what many supposed was an attempt to be the Joker. (It wasn’t; but that’s what many supposed.)

The Joker’s sympathetic origin story in “Joker” caused the families of Aurora victims to reflect. Five of them signed a letter to Warner Bros, urging the company to call for an end to political contributions to candidates who accept money from the National Rambo Association (NRA) and/or those who vote against gun reform.

The theater denied that it declined to show “Joker” because of the 2012 killings. But it’s difficult not to assume a connection.

SEAN MURPHY’S SEQUEL to his own comicbook creation bears DC’s “Black Label” seal, signalling some sort of beyond-routine excellence. The production itself reaches in that direction with slick paper and heavy-stock cover and the ostentatious “Book One” and “Book Two” instead of No.1 and No.2. And each issue previews its successor with reproduction in black-and-white of a few pages from the next issue.

SEAN MURPHY’S SEQUEL to his own comicbook creation bears DC’s “Black Label” seal, signalling some sort of beyond-routine excellence. The production itself reaches in that direction with slick paper and heavy-stock cover and the ostentatious “Book One” and “Book Two” instead of No.1 and No.2. And each issue previews its successor with reproduction in black-and-white of a few pages from the next issue.

The story also leaps far back in time to the English origins of the “Wayne empire,” an interesting but probably not essential flashback. We’ll see.

Otherwise, Book One begins with the present-day Joker’s escape from Arkham Asylum and the return of Batman’s dilemma at the end of the previous Murphy series: he wants to reveal his secret identity as Bruce Wayne to all of Gotham and the world. But numerous people, including police commissioner James Gordon, are repeatedly talking him out of it.

Meanwhile, the story disintegrates into the introduction of several new players: a black woman who seems to run things, a giant bearded guy dying of cancer who may be a relic of ancient Wayne history, and the Joker in various disguises while Napier denies that he is the Joker.

So far, tenuous bits of separate yarns, threatening threads that Murphy will eventually knit together. But at the moment, nothing but tantalizing fragments.

So far, tenuous bits of separate yarns, threatening threads that Murphy will eventually knit together. But at the moment, nothing but tantalizing fragments.

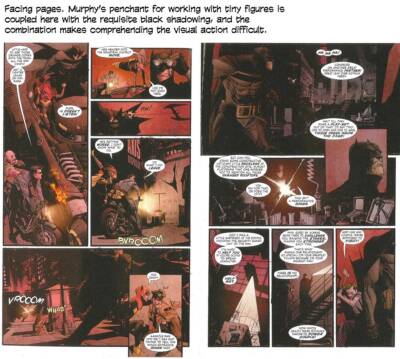

I’m a great admirer of Murphy’s visuals—exquisitely detailed renderings of people and places. And in this effort, he thankfully eschews the tiny tiny panels with tiny tiny detailed pictures that flawed the first White Knight by making the pictures nearly incomprehensible. Although he’s always leaning in that direction.

He continues, however, to indulge a fondness for drawing pictures of high-speed rolling stock, bristling with high tech armament.

And the Joker continues to fascinate.

- Funnies Farrago Celebrates a Half Century of Doonesbury - June 1, 2022

- Who Really Invented the Comic Character ‘Archie’? - May 7, 2022

- Dick Wright Returns - April 5, 2022