As we pause to celebrate the fact that Popeye is 90, we must also celebrate the comic strip in which the one-eyed sailor made his debut.

Popeye is 90. Actually, by the time you read this, he’ll be almost 91: his anniversary, strictly speaking, was in January 2019. But as we pause to celebrate the occasion, we must celebrate, too, the comic strip in which the one-eyed sailor made his debut. The strip was Thimble Theatre, and it first appeared 100 years ago on December 19, 1919. Yup: it ran for 10 years without Popeye.

Popeye is 90. Actually, by the time you read this, he’ll be almost 91: his anniversary, strictly speaking, was in January 2019. But as we pause to celebrate the occasion, we must celebrate, too, the comic strip in which the one-eyed sailor made his debut. The strip was Thimble Theatre, and it first appeared 100 years ago on December 19, 1919. Yup: it ran for 10 years without Popeye.

Thimble Theatre was supposed to parody movies and stage plays, and its creator E.C. Segar cast the strip with “actors” who would take parts in the lampoon productions: Willy Wormwood, a moustache-twirling villain akin to Desperate Desmond; the pure and simple heroine with a hysterical scream in her throat, Olive Oyl; and her stalwart (if not overly smart) boyfriend, Harold Hamgravy (who would soon lose his first name and become Ham Gravy). But after a few short weeks of daily or weekly productions along the intended line, Segar abandoned the original plan and focused instead on his actors and their real (as opposed to “reel”) adventures. And with the introduction shortly thereafter of Olive’s brother, the pint-sized Castor Oyl, the strip found its footing.

Castor Oyl was, in Segar’s words, “Olive’s foolish brother, not exactly half-witted but exceedingly dumb. Just this dumb: when Olive’s pet duck fell into a deep hole and no one could extricate it, Castor came by with a water hose and floated the duck to the top. He was clever in his own inimitable way. He even invented coal that would last forever, and he fireproofed safety dynamite so it couldn’t explode.”

Castor Oyl was, in Segar’s words, “Olive’s foolish brother, not exactly half-witted but exceedingly dumb. Just this dumb: when Olive’s pet duck fell into a deep hole and no one could extricate it, Castor came by with a water hose and floated the duck to the top. He was clever in his own inimitable way. He even invented coal that would last forever, and he fireproofed safety dynamite so it couldn’t explode.”

But Castor wasn’t merely kooky. He was maniacally ambitious. He wanted money and success, women and power. Having almost no special abilities that would enable him to achieve these ends, he pursued his aims with no more than single-minded, dogged determination. As an obsessive seeker after wealth and power, Castor was the perfect 1920s protagonist — a caricature of the materialistic go-getter, the icon of the age. He soon emerged as the star of the strip.

Castor’s greedy ambitions motivated the strip throughout the decade, one get-rich-quick scheme after another. Daily installments ended with comic punchlines, but the story of one day’s installment did not end with the last panel’s laugh: Segar strung the dailies together, stretching stories out for a week or more. Soon the stories meandered on for months, but such was Segar’s comic inventiveness that people enjoyed the ramble. One of Segar’s devices for creating suspense and maintaining interestingly comic continuity was to introduce wildly eccentric characters into his stories. The strip would focus for days — even weeks — on the Dickensian quirks and foibles of some minor character. As this character kept us entertained, Segar could, at the same time, inch his story along, day by day.

Popeye was one of these characters. And he brought out Segar’s creative genius.

In one of his get-rich-quick plans, Castor turns gambler. But not before he has a sure-fire system: his uncle has given him a Whiffle Hen, a good luck bird that guarantees winning at games of chance for anyone who rubs the three hairs on the bird’s head. Castor decides to take the Whiffle Hen to an offshore gambling hell called Dice Island and use the bird to fleece the gamblers. Castor buys a boat, but the boat has no crew, so Castor goes in search of one. And that’s what he hires: one–namely, Popeye. On January 17, 1929 (just ten days after Tarzan and Buck Rogers debuted), Castor approaches a one-eyed tattooed barnacle of a seadog with a corn-cob pipe standing on the dock, and he hires him.

“Hey there!” says Castor, “Are you a sailor?”

Confounded by Castor’s inability to perceive his occupation from his nautical garb and demeanor, the sailor replies with biting sarcasm: “Ja think I’m a cowboy?”

“Okay — you’re hired,” says Castor.

“Okay — you’re hired,” says Castor.

For the rest of Popeye’s origins, visit RCHarvey.com and subscribe to Rants & Raves; then click on Harv’s Hindsight; then scroll down until you get to March 2004 for “Popeye: A Masterwork in the Medium.” Here, however, we prolong our festivities by examining Popeye’s obsession with spinach.

IN POPEYE, readers saw a force for good that could not be defeated. And because he represented many of the country’s traditional values, his triumph in every encounter with evil reassured readers: if Popeye could win, those values were not bankrupt. However battered the economic and social institutions of the nation during the Great Depression, the fundamental values of its people remained viable. Thus, in this pragmatic comic sailor’s victories, Americans found immediate comfort and, perhaps, a prophecy: surely his successes foreshadowed the eventual return to happiness and prosperity of the society that subscribed to the time-tested values of small-town America.

Segar showed masterful skill in keeping his readership engaged with this concoction of comedy and morality, but it is likely that he enjoyed assistance from an unexpected quarter in initially enlisting the attention of much of his audience.

Segar showed masterful skill in keeping his readership engaged with this concoction of comedy and morality, but it is likely that he enjoyed assistance from an unexpected quarter in initially enlisting the attention of much of his audience.

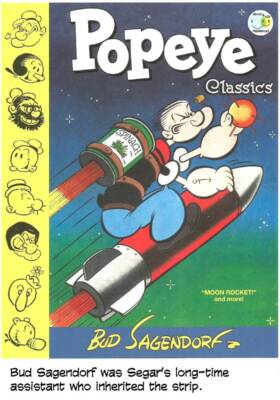

According to the late Bill Blackbeard, curator (and founder) of the San Francisco Academy of Comic Art, Thimble Theatre was not a widely published comic strip until the mid-thirties. Until then, Blackbeard says, it ran almost exclusively in Hearst papers. Yet by the end of the decade, Popeye was as widely celebrated a popular icon as Mickey Mouse. The circulation of the strip clearly increased dramatically during the latter part of the thirties. Much of the credit for that growth can be assigned to Segar’s genius in the practice of his craft, but some of the impetus to increase may be found in another medium altogether — the animated cartoon.

The first Popeye cartoon from the Fleischer Studios appeared in the summer of 1933, more than four years after Popeye’s arrival in the comic strip. If Blackbeard is correct about the limited circulation of the strip at the time (and his experience in searching out comic strips in thousands of old newspapers suggests strenuously that he is), then it is probable that it was the Fleischer Popeye that introduced the character to much of the American public. And Americans liked what they saw on the screen.

Popeye was an immediate hit, and the Fleischer brothers knew what to do with a hit: they produced more Popeye cartoons as fast as they could. Beginning in 1934, Fleischer Studios cranked out a Popeye cartoon every month for the next nine years. Cartoons starring either Popeye or Betty Boop comprised virtually the entire output of the studio for the rest of the decade.

The comic strip had surely been growing in circulation before the Fleischers started producing their Popeye cartoons: the Fleischers would not have been interested in such a property had it not demonstrated some kind of appeal. But the animated cartoons must have accelerated the dissemination of the strip. They catapulted Popeye smack into the public eye all across the nation — even in places where he didn’t appear in the newspaper. And the immense popularity of the cartoons created a demand for more Popeye.

Salesmen from King Features undoubtedly moved with alacrity to supply that demand with the syndicated Popeye newspaper comic strip, and the client list of newspapers running Segar’s strip increased apace. After that, it was up to Segar.

And he proved equal to the challenge: once before the reading public on the funny pages of the nation’s newspapers, Segar captured and held the interest and loyalty of his readers. Popeye’s popularity was scarcely due entirely to the Fleischers. The Popeye on the screen attracted public notice, but it was the Popeye in the papers that sustained it.

Segar’s Popeye and Fleischer’s are not exactly the same character. They are not identical. But they are so similar that the differences are complementary rather than contradictory. For one thing, the animated cartoons champion spinach as the source of Popeye’s strength.

Popeye’s passion for spinach is supposedly born out of one of history’s easiest mathematical errors, according to dailymail.co.uk.

In 1870, German chemist Erich von Wolf was researching the amount of iron in spinach and other green vegetables. When recording his findings in a new notebook, he misplaced a decimal point, making the iron content in spinach ten times more generous than in reality. While von Wolf actually found out that there are just 3.5 milligrams of iron in a 100g serving of spinach, the accepted number became 35 milligrams thanks to his mistake.

From that error arose the popular misconception that spinach, exceptionally high in iron, makes the body stronger.

If that were true, eating a generous serving of spinach would be comparable to munching on a small piece of paper clip.

Popeye’s animated cartoon creators, casting about, no doubt, for some novelty for the character, decided that spinach’s reputed ability to foster great strength would be the secret to Popeye’s strength. Every time he needed a burst of strength, he’d eat a can of spinach. It is believed that Popeye is responsible for boosting consumption of spinach in the U.S. by a third.

But in his newspaper comic strip incarnation, Popeye ate spinach only occasionally and evidently didn’t like it because he never made a habit of consuming it. Still, the Fleischers may have picked spinach because Segar once used it.

Segar had forced Popeye to consume a bowl of spinach on February 28, 1932, in preparation for a encounter with an iron-jawed braggart; the von Wolf factor supposedly gave Popeye enough iron to overpower the iron-jawed guy.

And that week’s episode concludes with a note from Popeye to mothers everywhere: “Please tell yer youngstirs I said they should eat spinach an’ vegebles on account of I wants ’em to be strong and helthy.” This may have been the origin of the spinach mythology that was taken up and magnified in the animated cartoons. But the erroneously high iron-content of the leafy vegetable doubtless established its viability as a strength enhancer.

Spinach figured more often in the strip’s stories after the advent of the animated Popeye, but the invigorating vegetable was seldom as integral to Popeye’s success in the strip as it was in the Fleischer cartoons.

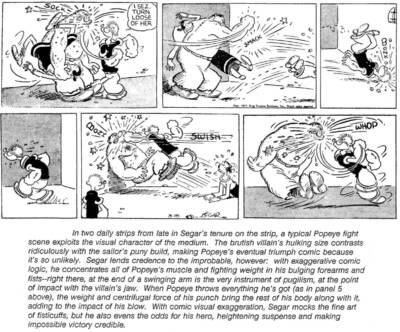

Segar’s forte in the daily strip continuity was prolonging Popeye’s idiotic predicaments; Popeye punched people out only after agonizing delay. On Sundays, the sailor took up prize fighting as an avocation and was often in the ring, socking his opponents. In the movies, however, Popeye’s very existence was defined by his pugilistic feat aided by spinach. And it was the animated Popeye that made Popeye famous, not Segar’s strip. But it’s the strip’s anniversary that we’re celebrating here this month. And the National Cartoonists Society joined in the festivities.

NCS celebrated the Popeye’s jubilee with an auction of original artwork by its members that will benefit the NCS Foundation.

Last winter, in the days leading up to the inaugural NCSFest in Huntington Beach, California, NCS members were asked to create original works of art in tribute to Popeye and his cast of characters for a special group exhibition at the Huntington Beach Art Center. The response was overwhelming and the exhibit was one of the highlights of the festival.

Last winter, in the days leading up to the inaugural NCSFest in Huntington Beach, California, NCS members were asked to create original works of art in tribute to Popeye and his cast of characters for a special group exhibition at the Huntington Beach Art Center. The response was overwhelming and the exhibit was one of the highlights of the festival.

Members were also asked if they would be willing to donate their original art for this special auction, and many agreed. Among the artists who donated original Popeye pieces are Patrick McDonnell, Jim Davis, Garry Trudeau, Lynn Johnston, Bobby London, Jeff Keane, Luke McGarry, Ann Telnaes, Mike Peters, Rick Kirkman, Jerry Scott, Jim Borgman, and many, many more!

To complete our celebration here in Rancid Raves, we’re reproducing some of the Popeye images herewith. How many of the contributing cartoonists can you identify? (Alas, their signatures are often illegible.) Enjoy.

Yes, there’s more to the story, but I promised only four pages, right?

- Funnies Farrago Celebrates a Half Century of Doonesbury - June 1, 2022

- Who Really Invented the Comic Character ‘Archie’? - May 7, 2022

- Dick Wright Returns - April 5, 2022