Three of DC Comics superheroes recently celebrated “Superbirthdays” — Superman, Batman and Wonder Woman.

Three of DC Comics superheroes recently celebrated anniversaries, or “Superbirthdays” — Superman, Batman and Wonder Woman. And DC dutifully brought forth a special birthday book for each of them.

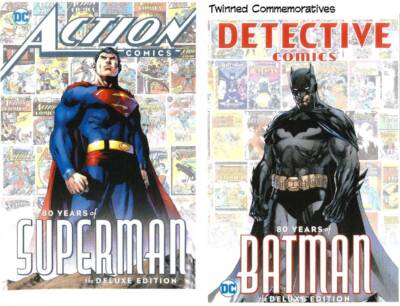

For all the successes of Action Comics: 80 Years of Superman, Deluxe Edition (383 7×11-inch pages, hardcover, $29.99), it is disappointing in one conspicuous aspect: it offers only one story drawn (penciled) by Wayne Boring, who in the late 1940s and throughout the 1950s established the “look” of the Man of Steel for a generation of readers. Boring created the barrel-chested Superman, a tradition continued by Al Plastino, who is represented in the next TWO stories, one featuring Supergirl. And she’s also the featured player in the next two, both drawn by Jim Mooney. Only two other stories are from the fifties, and only two stories penciled by Curt Swan, the darling of the 1970s.

For all the successes of Action Comics: 80 Years of Superman, Deluxe Edition (383 7×11-inch pages, hardcover, $29.99), it is disappointing in one conspicuous aspect: it offers only one story drawn (penciled) by Wayne Boring, who in the late 1940s and throughout the 1950s established the “look” of the Man of Steel for a generation of readers. Boring created the barrel-chested Superman, a tradition continued by Al Plastino, who is represented in the next TWO stories, one featuring Supergirl. And she’s also the featured player in the next two, both drawn by Jim Mooney. Only two other stories are from the fifties, and only two stories penciled by Curt Swan, the darling of the 1970s.

Superman’s earliest appearances are herein rehearsed in Action Comics Nos.1 and 2 1938), then the book skips ahead to No.42 (1941). Although the near-absence of Boring and the slight appearance of Swan suggests that this book is aimed chiefly at comicbook fans of the last 20-30 years, a cursory glance through the dates in the Table of Contents shows that every decade is about equally represented despite the slight to Wayne Boring.

The 21 stories in the book also include other characters who occupied the back pages of Action Comics (this isn’t, after all, “Superman Comics”: there are other characters “in action”). An excellent origin story for the Vigilante is drawn by Mort Meskin (still under the influence of Jack Kirby), and Fred Guardineer writes and draws a Zatara, Master Magician — stylistically stunning visually. There’s also a previously unpublished story by Superman creators Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster from 1945 in b/w, and from the 1970s, a crisply rendered (by Carmine Infantino and Dick Giordano) tale about Christopher Chance (written by Len Wein), “the human target” who stands in for those marked for murder, hoping he can stop the killer before he kills his assignment.

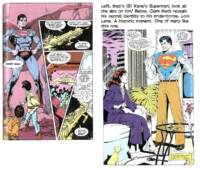

In the Superman stories, we meet the Toyman, Supergirl (“the world’s Greatest Heroine”), Bizarro, Wondergirl, Cyborg, and Silver Banshee, not to mention President Jack Kennedy. Clark proposes to Lois and marries her, and in another issue, reveals that he’s Superman before they can marry. Throughout, at intervals, artwork by John Byrne, Gil Kane, Neal Adams, and numerous others — notably, a special “double-sized anniversary issue” for No.800 with art by 17 artists.

At other intervals are essays by various personages: Laura Siegel Larson, creator Jerry Siegel’s daughter, who writes about the myth of the creation; longtime DC editor Paul Levitz, who also writes about the creation; Jules Feiffer on the first issue of Action Comics; Tom DeHaven on the times; Marv Wolfman on how he acquired the 12-page unpublished Superman story seeing print here for the first time; David Hajdu, Larry Tye, and Gene Luen Yang on other topics.

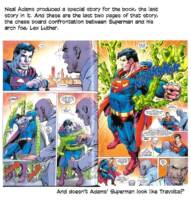

The final story is, I assume, produced especially for this volume. By Paul Levitz and drawn by Neal Adams, “The Game” has Superman (looking like a rugged John Travolta) and Lex Luther playing chess. Superman wins that game, but Luthor enchains him in Kryptonite. Still, Superman escapes. As always. This time, aided by Scott Free’s mother box.

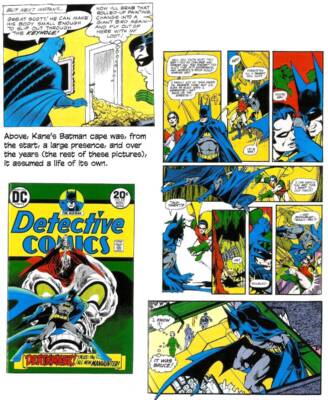

The last several stories are rendered in manners that are highly polished, highly computer-generated — more dazzle than anything else. Near here, I’ve salvaged some visual aids.

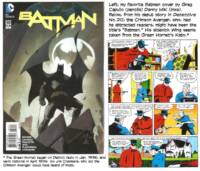

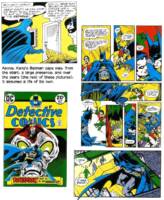

A glance at the cover art for Detective Comics: 80 Years of Batman, Deluxe Edition

416 7×11-inch pages, hardcover, $29.99) and that of the memorial to Action Comics establishes the now-obvious — companion tomes for DC’s greatest money-makers. Nice to see Bill Finger appropriately credited on the title page, joining, at long last, Bob Kane, the co-creator of the Cowled Crusader.

416 7×11-inch pages, hardcover, $29.99) and that of the memorial to Action Comics establishes the now-obvious — companion tomes for DC’s greatest money-makers. Nice to see Bill Finger appropriately credited on the title page, joining, at long last, Bob Kane, the co-creator of the Cowled Crusader.

The book’s 28 stories include the first Batman story from Detective No.27, May 1939 (as well as a 1976 tale woven around his maudlin origin, witnessing as a child the murder of his parents) and the debuts of Robin, Two-Face, Riddler (with Dick Sprang pencils), Bat-Woman drawn by Sheldon Moldoff (who pencils 3 stories herein, more than anyone else — 1956, 1959, 1961), Clayface, Batgirl (two-parter) and such sillinesses as Bat-Mite and Man-Bat, penciled by Neal Adams, who provided the definitive Batman visually for the 1970s (but not in this story). Sprang, who, with Moldoff, defined Batman in the 1950s, is criminally under-represented and Adams ditto. Bat-Mite gets a story but, strangely, no Joker story and no Penguin story.

As with the Superman tome, this volume is liberally laced with essays. Early, Paul Levitz recites an accurate history of DC Comics with the unscrupulous Harry Donenfeld wrenching the publishing company out of the hands of Major Malcolm Wheeler-Nicholson. Saith Levitz: “Batman is notable for the sheer range of brilliant interpretations he’s hand, and while not all the amazing writers and artists who have contributed to his history are represented here, many of the best are.” But not Frank Miller, whose Dark Knight tale reinvented the character and imbued him with psychological depth — and also encouraged a darker aspect to superheroes.

Senator Patrick Leahy, a Batman fan all his life, contributes an essay about his adventures with Batman in film cameos and on the Senate floor, where he passed out copies of the graphic novel about the horrors of landmines.

Other essays of fond recollection are by people who’ve worked on Batman or, mostly, been inspired by him (including the retiring chief of police in San Diego). Anthony Tollin details the pulp character inspirations for Finger and Kane.

While the emphasis of this volume is on Batman, Detective Comics featured other memorable characters, and several of them are present here. The first, the Crimson Avenger, was a masked do-goer who debuted in No.20 — seven issues before Batman — but didn’t make the grade and was discarded.

Others herein include the origin of Pow-Wow Smith, Indian Lawman (pencils by Carmine Infantino), Slam Bradley (a Captain Easy imitation by Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster), costumed Airwave with antena on his head and lightning bolt on his chest; Boy Commandos by Joe Simon and Jack Kirby; an episode of “Impossible But True” with Roy Raymond, a character who stars in the tv show of that name (well drawn by Ruben Moreira); Manhunter from Mars, and a Manhunter on Earth, two tales by Archie Goodman, stunningly rendered by Walt Simonson; and a Lew Sayre Schwartz sketchbook of page layouts (well-meant, no doubt, but meaningless without the final pages to compare them to).

The book ends with a tale produced especially for the volume, “Twenty-Seven,” by Scott Snyder, drawn in stunning detail with stroking pen by Sean Murphy, lays out a new Batman myth — of his regeneration in a new person every twenty-seven years, the number of years “he” has calculated “he” will be effective in fighting crime and evil in all its manifestations.

Now, a short gallery of pages and panels from the book.

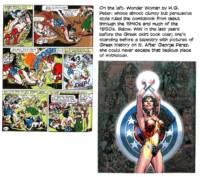

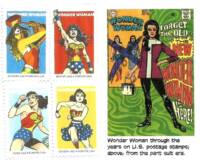

As in the other two commemorative tomes, the artist most associated with the character is decidedly under-represented in Wonder Woman: A Celebration of 75 Years (400 7×10-inch pages, hardcover, $39.99). Only 3 of the book’s 18 stories are drawn by H.G. Peter, who drew Wonder Woman through most of the 1940s and 1950s and whose somewhat awkward style defined the character. The reprinted stories are divided into four sections, each prefaced by an introduction that describes what happened during that period of Wonder Woman’s adventures. In the first, we learn of WW’s invention by William Moulton Marston, a psychologist who lived with a wife and in-house mistress (this domestic arrangement, however fascinating, isn’t mention in this all-ages tome).

The second section presents the most awful of WW’s history — when she lost her powers, her costume and her link with the mysterious Amazon Island where she was “inconceivably conceived” (to quote one story introduction), born, and raised. For five years (1968-1973), WW was only Diana Prince, a private investigator in a white pantsuit with a fashion store as cover and expertise in judo. This section concludes with a 1982 story in which WW’s costume gets some revision, including the imposition of a new eagle-less ww on her chest.

In 1987, George Perez, then a fan favorite artist, took over both writing and drawing WW. The book gives him only one story — a tedious “history” of Greek mythology on Amazon Island, where — at last, by the end of the story — Diana emerges as WW. Then William Messner-Loebs took over for a while, but Wonder Woman after Perez is forever burdened with histories of Amazon Island and pseudo mythology. Boring.

Wonder Woman “showed as many faces as Diana herself” in the creative teams that followed. Judging from the Table of Contents listing, no artist or writer made the character his/her own. And the character was always in flux — now a warrior, next a philosopher — her appearance changing from the cartoony (but lively) treatment of J. Bone to the bulging superheroine physique of Ethan Van Sciver and everything in between.

Management could never make up its minds about WW’s appearance: should she be sexy or more school-marmish? Management could never make up its minds about Wonder Woman in general. What was her character anyhow? Who was she supposed to be — superheroine or Greek princess? Or pinup queen? The book satisfactorily represents this decades-long confusion and indecision.

Management could never make up its minds about WW’s appearance: should she be sexy or more school-marmish? Management could never make up its minds about Wonder Woman in general. What was her character anyhow? Who was she supposed to be — superheroine or Greek princess? Or pinup queen? The book satisfactorily represents this decades-long confusion and indecision.

Despite my carping about the miserable under-representation of Wayne Boring and H.G. Peter, this trio of commemorative volumes does a respectable job of representing DC’s headline characters over several decades of their existence. No DC comicbook fan should be without them.

- Funnies Farrago Celebrates a Half Century of Doonesbury - June 1, 2022

- Who Really Invented the Comic Character ‘Archie’? - May 7, 2022

- Dick Wright Returns - April 5, 2022