His iconic signature could be found in magazines, comic books and comic strips. Funnies Farrago on Henry Boltinoff.

Henry Boltinoff died April 26, 2001. He had been a cartoonist all his life, since about 1933. That’s 68 of his 87 years. He was one of the last of a vanishing breed — the cartoonists who began working in the 1930s and worked in every venue of cartooning, magazines and comic books and newspaper comic strips. And his signature was one of the best-known in the business.

He didn’t sign his name big, but it was still a very visible signature. Clearly printed. You saw it everywhere.

He didn’t sign his name big, but it was still a very visible signature. Clearly printed. You saw it everywhere.

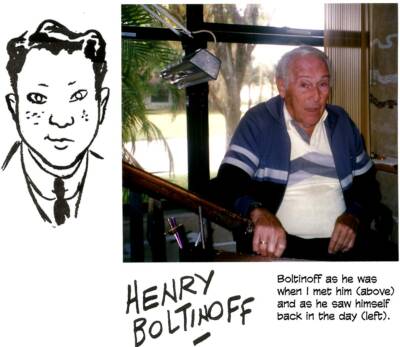

I met Henry Boltinoff on February 14, 1998. I was down in Boca Raton, visiting the International Museum of Cartoon Art (since closed) to assemble original art for an exhibit at the Frye Art Museum in Seattle, Washington. And while I was in the neighborhood, I thought I’d call on various cartoonists who lived in the vicinity. I asked Jud Hurd, editor/publisher of Cartoonist PROfiles, who was around there, who he’d like a story on; and he suggested Henry.

So I went to his place at Lake Worth, a snug little townhouse in English Court. He lived alone, his wife having died in about 1992. They’d been living full-time in Florida only about four years at the time. At first, they’d go to Florida for several months of the year, then return to the New York area. But, Henry said, his wife put her foot down at last. Tired of packing and unpacking, she said, Let’s move to Florida. So they did.

We talked for an hour or so and then went to lunch. Driving with Henry was somewhat harrowing: he didn’t steer so much as he lunged, veering sharply — suddenly — off in whichever direction he chose. But we didn’t run into anything. Which proves that prayer works.

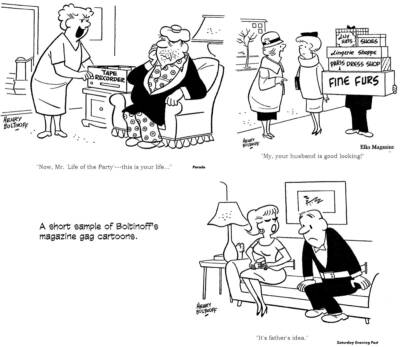

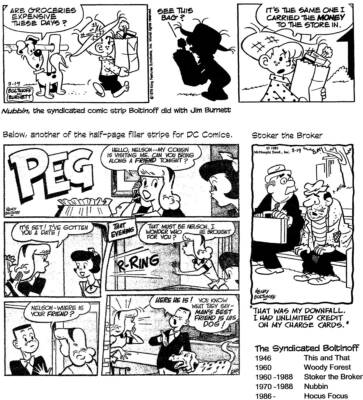

For about a decade, Henry Boltinoff was producing Stoker the Broker, a newspaper panel syndicated by Washington Star Syndicate (and then McNaught); full-page and half-page comic strip fillers for National Periodicals comic books (now DC Comics); and panel cartoons for magazines like Saturday Evening Post, Look, Collier’s, Ladies Home Journal, and the like.

For about a decade, Henry Boltinoff was producing Stoker the Broker, a newspaper panel syndicated by Washington Star Syndicate (and then McNaught); full-page and half-page comic strip fillers for National Periodicals comic books (now DC Comics); and panel cartoons for magazines like Saturday Evening Post, Look, Collier’s, Ladies Home Journal, and the like.

You saw his signature in all those places. Henry stacked on Boltinoff. With a neatly placed underscoring just under the middle of the last name. And the drawings were just as meticulously rendered — tight drawings, judiciously placed black solids.

You saw the signature even in the comic books, which at the time didn’t usually print the names of the cartoonists or writers who produced their content. But Boltinoff signed his work. “If I do a drawing and it appears in print,” he said, “I want my name on it.”

Now, in February 1998 when I visited Henry Boltinoff in his Florida hideaway, the signature is still as tidy as ever. And so are the drawings. He sits at an antique pedestal drawing table in one of the two bedrooms of his apartment with the windows on his right, drawing Hocus Focus, a daily panel for King Features.

Now, in February 1998 when I visited Henry Boltinoff in his Florida hideaway, the signature is still as tidy as ever. And so are the drawings. He sits at an antique pedestal drawing table in one of the two bedrooms of his apartment with the windows on his right, drawing Hocus Focus, a daily panel for King Features.

“It’s a little puzzle,” he explained. “Two pictures. The second picture has six different details from the first. You’re supposed to find them. Not a big thing. I send it up every two weeks; every two weeks, they send me a check. If I sat down from nine to five to do a whole week’s work, I’d do it all in a day and a half. So I work at my own pace. I usually work two hours here, two hours there. I take a break. I take it easy.” He grinned. “I play tennis.”

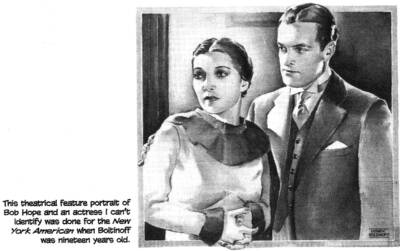

Boltinoff has been doing Hocus Focus since about 1986. He started drawing for newspaper reproduction in 1933. He was nineteen and attending classes at the Art Students League in New York City. His brother Murray was assistant drama editor at the New York America, and Henry did theatrical portraits for the paper. He was paid by the column, $25 for a two-column picture, two a week. When the paper suddenly started asking for four-column pictures, Boltinoff’s salary doubled.

When the American folded in 1937, Henry Boltinoff was out of work. He turned to two high school classmates, George Wolfe and Ben Roth, both cartoonists, who were sharing a studio. They advised him to start doing cartoons for magazines.

When the American folded in 1937, Henry Boltinoff was out of work. He turned to two high school classmates, George Wolfe and Ben Roth, both cartoonists, who were sharing a studio. They advised him to start doing cartoons for magazines.

“They said, Do a batch of roughs, about 10-15 a week,” Boltinoff recalled. “We’ll meet you on Wednesday and take you around, they said. In those days, you could make a living doing magazine cartooning. Today, I don’t know what you could do. But Wednesday in New York was ‘Look Day’ then: cartoon editors looked at your submissions if you brought them in personally. You could spend the whole day Wednesday, going from one magazine to another. There were that many magazines. The Saturday Evening Post was printed in Philadelphia, but the cartoon editor came in every Tuesday night to see the cartoonists on Wednesday morning.”

Cartoonists went from office to office, sitting in waiting rooms, waiting; then showing their wares to stone-faced cartoon editors.

“One time, I was going around with George Wolfe,” Boltinoff said, “and we went in to see Gurney Williams at Collier’s. I’d just become a father. My first child. A few days before. So I said to Gurney Williams, I just became a father — congratulate me. And he said, Congratulations. And I handed over my roughs. He looked through them. Handed them back and said, Better luck next time. George couldn’t believe it. And he went in and said to Williams, Just to show you’re a nice guy, hold out one or two — you don’t have to take them. The next week they can be rejected. But you don’t slap a guy in the face like that when he just became a father.”

Most cartoonists submitted roughs on Look Day. If an editor liked one or more, he’d ask for a finished drawing. Or he might “hold” a rough until the next week. When the cartoonist returned the next Wednesday, the editor either returned the rough, rejected, or asked for finished artwork.

For lunch, all the cartoonists would gather at the Pen and Pencil, a former speak-easy on 45th Street near Third Avenue. John Bruno had started the bistro during Prohibition, and when adult beverages became legal again in 1933, he applied for a restaurant license. For the application form, he needed a name for the place. He asked his patrons for advice. Most of them were newspaper men and cartoonists. Cartoonist Gil Fox told me that he suggested the name Pen and Pencil because that described the tools of the trade of those who frequented Bruno’s.

Every Wednesday the magazine cartoonists took a mid-day breather and a beaker or two over lunch at the Pen and Pencil. Despite their being competitors — each one visiting and trying to sell cartoons at the same magazines (so if one cartoonist sold a cartoon at one place, the chances of another cartoonist selling there were reduced accordingly) — they didn’t feel cut-throat about it, Boltinoff said. In fact, one time when he had to be out of town on a Wednesday, he gave his batch to his friend George Wolfe, who took them around. He’d show his batch first; then Boltinoff’s batch.

I reminded Boltinoff that Charles Schulz had started by doing magazine cartoons. Schulz always thought kindly of John Bailey, the cartoon editor at The Saturday Evening Post, for giving him advice about his work.

Henry Boltinoff remembered Schulz coming to the Pen and Pencil one Wednesday. “He didn’t remember this when I mentioned it some years ago,” Boltinoff said, “but he came in, and he wasn’t wearing a tie; he had an open sport shirt on. And the head waiter told him, You need a tie; I’ll get one in the office. In those days, for people who didn’t come properly dressed, the head waiters kept a cotton jacket and an old tie in the office that they’d let you wear. But George Wolfe said, Don’t bother. And he took out a dollar bill, twisted it like a bow tie, and he put it on Schulz with a paper clip. Schulz gave it back to him later. Nowadays, ties aren’t that important.”

Once, Boltinoff told me, McGowan Miller, an habitué of another New York cartoonists hangout called the Palm, came over to the Pen and Pencil during one of the Wednesday gatherings and asked all the magazine cartoonists if they would meet the next Wednesday at the Palm over on Second Avenue, a block or so away.

The Palm’s walls had been decorated over the years by syndicated newspaper cartoonists (Milton Caniff, George McManus, Jimmy Hatlo, Billy DeBeck, Fred Lasswell, and so on); they drew their characters on the walls, and the restaurant made quite a production out of its merry murals.

The Palm had just opened a new upstairs room, and the walls were bare. Mac Miller invited the magazine cartoonists to decorate the walls. Just put up pencil sketches, he said; he, Miller, would paint them afterwards. And the Palm would stand them all to drinks that day and their lunches.

So the next week, they all went to the Palm. They drank and ate. They drank and ate well. And they put pencil sketches on the walls.

The following week, they were all back in the Pen and Pencil. Then Mac Miller came in. Very shame-faced. “I’m embarrassed,” he said. And he explained that the Palm had a new busboy, a kid who didn’t speak English well. And when he came into the upstairs room that the cartoonists had lunched in, he saw the mess on the walls. And he cleaned it all off.

So they all went back over the following Wednesday for another free lunch and drinks.

The Palm with its decorated walls is still there; and, until a year or so ago, so was the Pen and Pencil. But now it’s gone. And so’s Costello’s, a favorite of Walt Kelly’s and James Thurber’s.

In making the rounds, the cartoonists started at the offices of the highest paying magazines and worked down the pay scale.

“Look paid a lot,” Boltinoff remembered. “I never went to The New Yorker. It was never my cup of tea. I never liked it. I remember years ago in The New Yorker, there were great cartoonists. Each one was a great artist himself. Robert Day, Richard Decker, Richard Taylor, Peter Arno, George Price — everybody had a different style. Good artwork. And now the stuff — well, I don’t like it much now.”

Selling cartoons to magazines is a highly speculative undertaking, and when Henry Boltinoff got married in 1940, he felt he needed a more regular source of income, so he turned to comic books. He went to National Periodical Publications because he knew the editor, Whitney Ellsworth.

“Whit said, Do a couple filler pages — whatever you want,” Boltinoff said. “In those days, comic books were 64 pages with no advertising. So there was plenty of room for a filler. Now the books are 32 pages and they take advertising. I started doing some work for him. I did it for almost thirty years.”

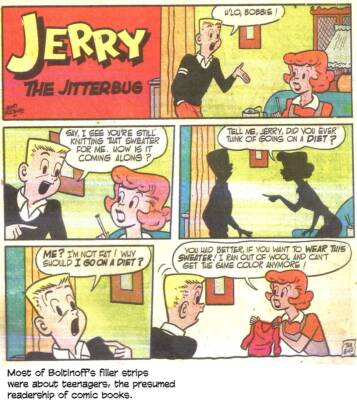

The fillers were half-page, full-page and occasionally 2-3 page comic strips. Anyone collecting comics from the 1940s through the 1950s is familiar with his pictures and his signature. Boltinoff wrote them, drew them, and lettered them. The strips were named after a host of protagonists: Jerry the Jitterbug, Varsity Vic, Cora the Car Hop, Peg, Ollie, Moolah the Mystic, Private Pete, Shorty, Tricksy, Dover and Clover, Homer, Casey the Cop, Bebe, and so on. In the 1960s, he was also doing Cap’s Hobby Hints, which was aimed at model builders and the like.

The fillers were half-page, full-page and occasionally 2-3 page comic strips. Anyone collecting comics from the 1940s through the 1950s is familiar with his pictures and his signature. Boltinoff wrote them, drew them, and lettered them. The strips were named after a host of protagonists: Jerry the Jitterbug, Varsity Vic, Cora the Car Hop, Peg, Ollie, Moolah the Mystic, Private Pete, Shorty, Tricksy, Dover and Clover, Homer, Casey the Cop, Bebe, and so on. In the 1960s, he was also doing Cap’s Hobby Hints, which was aimed at model builders and the like.

Boltinoff did several filler page strips a week, submitting roughs for approval first. And he was able to pay his brother back for getting him the assignments at the American.

One day Ellsworth was grousing about his job, saying the work was getting too much; he needed an assistant. Boltinoff told him about his brother, who had been working for a public relations firm since the American folded.

“I said, My brother’s a writer; I’ll send him up. And he went up there, and he got a job, and he stayed there over 50 years.”

But having a brother as an editor didn’t give Henry Boltinoff any advantage when it came to getting his filler page submissions approved.

“It was tougher with him there,” Boltinoff said. “They had other editors. I got work from this editor, and from that editor. The toughest guy was my brother: I always had to submit a rough for approval. When he put something into a comic book with my name on it, he wanted to make sure it was a really good gag. He didn’t want people to say, Ahh, you print this crap because your brother did it. So he was in a spot. And, of course, so was I,” he finished with a laugh.

One of Boltinoff’s filler pages reappeared in a 1990 book of reprints from DC called The Greatest 1950s Stories Ever Told. His filler was Casey the Cop. “I got paid for this reprint,” he told me. “I got more for the reprint than I did for the original artwork!”

He sometimes did whole stories for comic books. “They asked me if I’d like to write for some of the teenage titles — like A Date with Judy,” he said. “I would figure out a theme, write a whole bunch of gags about it, and then piece them all together into a story. I found one advantage in writing your own stuff is that you never write scenes calling for very complicated drawings,” he laughed.

While doing filler pages for National, Boltinoff continued doing gag cartoons for the magazines. But both magazines and comic books began cutting back in the late 1950s. In 1960, Boltinoff was glad to undertake a project suggested to him by a small syndicate, Columbia Features. This was Stoker the Broker, a daily gag panel about the business world, which would be marketed as a feature for newspapers’ financial section or stock report page. Boltinoff had attempted a couple of short-lived syndicated features before, but this one, as it turned out, lasted.

“Once an editor told me he couldn’t see a cartoon in the financial section,” Boltinoff said. “Business was too serious. I told him the first editorial cartoon probably got the same reaction. And now if you don’t see a cartoon, it’s not an editorial page.”

Stoker the Broker lasted thirty years. It’s longevity is even more remarkable considering that Boltinoff never liked doing it much.

“What’s funny about the stock market?” he said. “I knew nothing about the stock market when I started it. I learned, though. But writing the gags was a pain.”

Then in 1970, he was invited to replace George Crenshaw as the artist on Nubbin, a comic strip about a farm kid written by Jim Burnett. By this time, the teenage comic books were gone, so Boltinoff welcomed the opportunity and continued producing the strip for almost twenty years.

Then in 1970, he was invited to replace George Crenshaw as the artist on Nubbin, a comic strip about a farm kid written by Jim Burnett. By this time, the teenage comic books were gone, so Boltinoff welcomed the opportunity and continued producing the strip for almost twenty years.

With a track record on individual features that runs for decades, Boltinoff can’t understand Bill Watterson and Gary Larson, who quit their features after relatively short runs.

“Temperamental guys,” he said. “I don’t know what they were doing before they did strips, but a guy like me in the magazine business, for years, you go along, week to week, you don’t know whether you’ll get a rejection slip or an okay. And here’s somebody has a syndicated feature — you do what you want, and you get paid regularly every week, and they give it up. It came too easy. They don’t appreciate it.

“They said they burned out,” Boltinoff continued. “But if you’re overworked, you do what most cartoonists do — you hire somebody to help. No one does it all by himself. Milton Caniff had guys helping. Frank Engli did the lettering. The only guy who’s done his own by himself is Charlie Schulz. No assistants, he says; I do it myself. But his strip is easier to do than Milton Caniff’s. That’s something to draw! All those backgrounds. But Charlie Schulz said, When I die, that’s the end of the strip. But I say, if you die, why should you deprive your family of a nice income? United Feature can hire a guy to write it and someone else to draw it.

“When Chic Young who did Blondie died, his son, Dean, took over and writes it,” he said. “Dean Young lives down here, around Tampa. And they got Stan Drake to draw it. Wonderful artist. Used to do The Heart of Juliet Jones. Wonderful. And he started to do Blondie. I spoke to Bill Yates, who was cartoon editor then up at King, and I said, How the hell does Stan Drake sit and draw like Chic Young after doing all that realistic stuff he did? So Bill says, I guess he likes to eat.”

Nowadays, the artist of record on Blondie is John Marshall; but he doubtless has at least one unnamed assistant. Dean Young acts as the strip’s manager: he sorts through ideas submitted by others and picks the ones Marshall is to draw.

Nowadays, the artist of record on Blondie is John Marshall; but he doubtless has at least one unnamed assistant. Dean Young acts as the strip’s manager: he sorts through ideas submitted by others and picks the ones Marshall is to draw.

Playing tennis three times a week, Henry Boltinoff is six months ahead on Hocus Focus.

“I showed my daughter where the finished drawings are,” he said, smiling, “up there, on that shelf in the closet. If something happens to me, she can send the stuff in, and she’ll have six months of money coming in. It’s like an extra life insurance policy.”

As of April 2001, regretfully, she began cashing in on that insurance policy.

- Funnies Farrago Celebrates a Half Century of Doonesbury - June 1, 2022

- Who Really Invented the Comic Character ‘Archie’? - May 7, 2022

- Dick Wright Returns - April 5, 2022