Funnies Farrago examines “Modesty Blaise and Peter O’Donnell” – the last great adventure comic strip!

He calls her “Princess,” and that, it turns out, is the consummate expression, for him, of their relationship. She calls him “Willie love,” but that, for American readers, is misleading: they aren’t lovers. For readers in their native Britain, however, “love” here represents not fevered ardor but a kind of familial affection, and that is an almost complete description, to her, of their relationship.

To me, Modesty Blaise and Willie Garvin are a literary pair that ranks with Damon and Phintias. Or Roland and Oliver. Sherlock Holmes and Doctor Watson. Don Quixote and Sancho Panza. But Modesty and Willie are a greater literary achievement than these more celebrated duos: they are more fully rounded, more human. Their personalities have depth and nuance. They live. For a potboiler pair, that’s a notable feat.

To me, Modesty Blaise and Willie Garvin are a literary pair that ranks with Damon and Phintias. Or Roland and Oliver. Sherlock Holmes and Doctor Watson. Don Quixote and Sancho Panza. But Modesty and Willie are a greater literary achievement than these more celebrated duos: they are more fully rounded, more human. Their personalities have depth and nuance. They live. For a potboiler pair, that’s a notable feat.

Peter O’Donnell concocted Modesty and Willie as characters in a comic strip of stylish cloak and dagger intrigue for a London newspaper. The strip, Modesty Blaise, followed the clandestine adventures of the voluptuous and superbly athletic Modesty, a retired and fabulously wealthy erstwhile leader of an international crime network who now devoted her considerable talents for lethal undercover work to helping the British secret service, which she did with the able assistance of her comrade in arms, Willie Garvin.

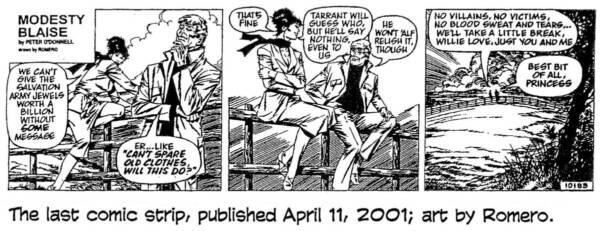

Modesty and Willie were also incarnated in 13 novels and two collections of short stories where their personalities were more fully fleshed out than in the strip. On April 11, 2001, the comic strip ended after almost 38 years, 10,183 individual daily strips. And O’Donnell had said, with the publication of the book The Cobra Trap in 1996, that he would write no more novels about Modesty Blaise. But that is scarcely the end of Modesty and Willie.

Like any other literary creations, they will live on in the works that gave them life. The novels are still on shelves in bookstores, waiting to be purchased and read. And Comics Revue started re-running the strip in December 2005 with issue No. 188. (Subscriptions are $59 for 12 monthly issues from Manuscript Press, P.O. Box 336, Mountain Home, TN 37684.)

Like any other literary creations, they will live on in the works that gave them life. The novels are still on shelves in bookstores, waiting to be purchased and read. And Comics Revue started re-running the strip in December 2005 with issue No. 188. (Subscriptions are $59 for 12 monthly issues from Manuscript Press, P.O. Box 336, Mountain Home, TN 37684.)

I first heard of Modesty Blaise in the mid-1960s, right about the time the movie starring Monica Vitti appeared, I suppose, which would make it 1966. By all accounts from Modesty fans, it was a terrible movie. O’Donnell said it gave him a nose bleed. Vitti, a blonde Italian actress, insisted upon remaining a blonde in the movie; Modesty has dark hair. And there was ample other silliness. Leonard Maltin’s Movie and Video Guide says this about it: “Director Joseph Losey ate watermelon, pickles, and ice cream, went to sleep, woke up, and made this adaptation of the comic strip about a sexy female spy.”

From the ballyhoo about the movie, I concluded that Modesty Blaise was a female James Bond. And when, subsequently, I heard about the comic strip, I assumed, from what I heard, that its main attraction was that Modesty was often nude. Like another notorious British comic strip, Jane.

In both of these notions, I was mistaken. The movie makers may have sought to capitalize on the popularity of the Sean Connery flicks by claiming Modesty was a female version of Ian Fleming’s 007. But Modesty Blaise is a much more complex and fascinating character than James Bond ever was.

As for the charge of nakedness—overwrought. Modesty sometimes strips to bra and panties when she’s caught in a dangerous situation while attired in ordinary street clothes. But that doesn’t happen often. Usually, she goes into action deliberately, seeking out some dastardly villain she’s been alerted to. And for such forays, she dons a black jump suit that covers her from head to toe.

No, the attraction—what holds me enthralled still—about Modesty Blaise is neither nudity nor Bonded gender change. Instead, it is the ingenuity of O’Donnell’s plots—their inventiveness, their twists, the tenterhooks upon which O’Donnell suspends his readers—the intelligence of his stories and their devices, the novelty of his characterizations, and the transcendence of the partnership between Modesty and Willie, their romance without romance.

I own all the novels, but I haven’t read them all. I have deliberately put off reading the last couple that I bought because I know that after I read them, there will be no more freshly minted Modesty novels to read. I’ll have exhausted this rich vein of adventure stories. And I want to postpone that unhappy moment as long as I can. Perverse of me, I know. But love is about longing as well as consummation.

But enough about me. Let’s talk about Modesty and her history as derived, chiefly, from the novels.

By the time all of the stories about Modesty Blaise begin, she has been retired for some time from her previous occupation as the head of an international criminal organization known as the Network. The Network specialized in theft. Modesty, who was orphaned as a child in the aftermath of World War II and survived a hard-scrabble hand-to-mouth existence through the sheer ferocity of her determination, refused to deal in vice or drugs: she loathed human degradation and those who dealt in it.

When Modesty first saw Willie Garvin, he was a gutter-bred bitter self-hating rough-neck hoodlum. But she saw in him not only prodigious physical abilities but impressive mental prowess and, presumably, a kind of innate stalwartness. She rescued him from his thug’s lowlife and gave him the opportunity to make something of himself. And in six months, a new Willie Garvin emerged—a man of cheerful confidence and sharp intelligence with all his former criminal skills enhanced by his knowledge that someone believed in him—Modesty. On the day they met, when Modesty bought him out of jail, she seemed a “Princess” to Willie; and he has called her “Princess” ever since.

Through the six years they worked together in the Network, “they schemed, fought, bled, tended each other’s hurts,” and, in effect, became halves of a single personality, so attuned that each knew what the other was thinking and would do under any circumstance. And then, having piled up a small fortune apiece, they retired. Modesty split up the Network among her lieutenants and bought a penthouse in London; Willie took possession of an old-world pub by the River Thames.

But they were not content with their new humdrum existence, and so when Sir Gerald Tarrant of British Intelligence needed some unorthodox help in an enterprise that was, for him, illegal, he turned to Modesty and Willie. They helped Tarrant on that occasion and liked the work well enough to take other assignments as they cropped up. And those comprise the Modesty Blaise oeuvre of Peter O’Donnell.

Until Modesty came along, most of O’Donnell’s writing was in comics. He sold his first story in 1936 when he was sixteen to The Scout, one of many magazines manufactured in England for young readers. He became a staff writer for the publisher of such magazines in 1937, turning out stories for both serious and humorous “picture stories” (comics). His career was interrupted for six years by World War II, in which he served as a radio operator. Upon discharge in about 1945, he became a book publisher for a few years and then, in 1951, returned to freelance writing, producing many stories for the magazines of Amalgamated Press (the forerunner of Fleetway Publications).

In 1953, an Amalgamated editor recommended O’Donnell as a substitute writer for a newspaper comic strip called Belinda. While he was doing that, he was invited to take over writing Garth, a science fantasy strip that had slipped in popularity. O’Donnell revived it, and soon after starting on it, he was also doing Tug Transom, a strip about the skipper of a tramp steamer and his crew. During the 1950s, he also wrote a couple of other more humorous strips—For Better or Worse (about a married couple, Jack and Jill) and Eve (another Jane, England’s notorious strip about a young woman who manages to undress on camera frequently)—and short stories for women’s magazines.

Then at the end of 1956, the Daily Mirror lost the artist-writer of one of its most popular strips, Romeo Brown.

In England, newspaper strips are produced for individual newspapers, not syndicates; popular strips may be circulated to “provincial papers” by the London papers that own them, but not always. Many strips appear only in their “home” newspapers where they were born. I don’t know if Romeo Brown appeared anywhere except in the Daily Mirror, but when the Daily Sketch lured Alfred Mazure (“Maz”) away, the Mirror needed someone to write Romeo Brown and someone to draw it. O’Donnell was invited to write it, and to draw it, the Mirror hired the man O’Donnell would thereafter always refer to as “the great Jim Holdaway,” the artist who would, later, give Modesty Blaise her glamorous appearance.

Romeo Brown was a blundering comical detective out of P.G. Wodehouse, but the strip’s “main idea,” O’Donnell said, “was to get girls’ clothes off in the nicest possible way.”

Romeo Brown was a blundering comical detective out of P.G. Wodehouse, but the strip’s “main idea,” O’Donnell said, “was to get girls’ clothes off in the nicest possible way.”

Later, O’Donnell learned that Holdaway was plunged into despair when he found out what Romeo Brown was about. “He went home and said to his wife, ‘I can’t do this—I can’t draw girls.’ He had been drawing westerns for a long time and thought that he could draw only cowboys and horses!”

It soon developed, however, that Holdaway could draw pretty girls very well. Sexy, beautiful girls. Well enough that when O’Donnell invented Modesty Blaise—a beautiful, sexy heroine—he wanted Holdaway to draw her. Initially, the publishing newspaper tried another artist, but that individual “totally misunderstood” the character. “It was a disaster,” O’Donnell said. He promptly recommended Holdaway, and Modesty was, forthwith, given visual life.

Modesty Blaise began in the London Evening Standard on May 13, 1963, but O’Donnell’s heroine had been lurking in the back corridors of his imagination for many months prior to that. After a decade of producing stories for he-men like Garth and Tug Transom while also writing romantic fiction for female readers, O’Donnell had started thinking about combining the two somehow in “a super woman who could have the kind of adventure the big, super male heroes had been having all this time—that was the beginning.”

In an interview with Nick Landeu in Comic Media (March 1973), O’Donnell explained: “You let these things simmer. You don’t consciously think about them very often. But gradually the yeast seems to work, and a character emerges. I would say that until you actually start to write the characters—to put dialogue in the mouth and to activate the strings of the [puppet]—they don’t come to life. Not for me at any rate. I can only get so far in thinking about a character, and then I’ve got to start working them out—writing pages and pages of dialogue and action just to get the blood flowing through the veins—and then they’ll begin to take on life for themselves and sometimes surprise me with what they say or do.”

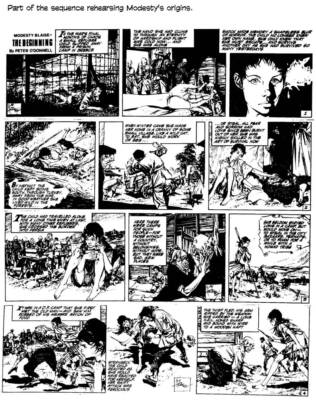

In imagining such a “super woman” as Modesty, O’Donnell had to give her a background, a history, that would make her plausible. “I don’t think you could take a girl from behind a counter in a shop and turn her into a Modesty Blaise. It had to be born in the blood and the bone.”

He remembered, then, an incident from his army career. As he has told it frequently, he was with a mobile radio detachment in northern Persia in 1942, eating his dinner out of a mess kit beside a small stream when “this child suddenly appeared. She was alone, she was barefoot, she wore a rag of a dress, she had all her belongings tied up in a blanket on her head, and she had a cord around her neck with something hanging on it. She sat down at some distance away, on the other side of the stream, and started gnawing on something she removed from her bundle.”

O’Donnell and his comrades offered the girl food, and she finally took some, warily. O’Donnell saw that the object on the cord around her neck was a piece of wood with a long nail lashed to it—“a weapon, which she obviously needed.”

O’Donnell “surmised that she was a refugee from somewhere in the Balkans, and she had been on her own for some time because she was unfazed, she was her own person, this little kid,” and after eating from the mess kit she’d been given, she washed the utensils in the stream, using sand to scour them. “She stood there for a few seconds,” he continued, “and then she gave us a smile, and you could have lit up a small village with that smile, and then she said something and walked off into the desert, going south, and she was on her own and walked like a little princess. I never forgot that child. And when I wanted a background for Modesty Blaise, I knew that child was the story.”

But Modesty is an extremely knowledgeable and sophisticated woman of the world, and for that aspect of her character, O’Donnell put the refugee girl in the company of an old man, a Hungarian professor, whom the girl protected. And he educated her. After he died, Modesty was 16 or 17, and she heard about a casino in Tangier and went there to work. There, presumably, she acquired some social polish and learned much about the shadowy underworld, and when her boss was killed, she took over his operation, eventually forming the Network.

But Modesty is an extremely knowledgeable and sophisticated woman of the world, and for that aspect of her character, O’Donnell put the refugee girl in the company of an old man, a Hungarian professor, whom the girl protected. And he educated her. After he died, Modesty was 16 or 17, and she heard about a casino in Tangier and went there to work. There, presumably, she acquired some social polish and learned much about the shadowy underworld, and when her boss was killed, she took over his operation, eventually forming the Network.

“Once Modesty had fully emerged,” O’Donnell said, “the totality of Willie Garvin followed thirty seconds later. He is an essential part of her.”

It remained only to give his heroine a name. In a 1996 letter to Bill Wottlin, O’Donnell rehearsed the story of Modesty’s christening:

“The name Modesty Blaise emerged for me long after devising the character. I was looking for a dramatic name but nothing appealed. Then one day I was typing a script for Garth when I mis-typed the adverb ‘modestly’ and it came out ‘modesty.’ That’s when it hit me that this would be the ideal antithetic forename for her.

“At the time,” he continued, “I was reading a book by C.S. Lewis. It was called That Hideous Strength and featured the resuscitation of Merlin from the days of the Arthurian legend. It was here that I learnt that Merlin’s tutor was a magician called Blaise. This was a monosyllable (as required for cadence), and it also had a fiery ring to it. So she became Modesty Blaise.”

The Modesty Blaise novels began with the Losey movie. Initially, the idea was to promote the movie, and O’Donnell simply adapted the screenplay he’d written. But the final screenplay was re-written several times, leaving only one line from O’Donnell’s script; so the first novel, Modesty Blaise (1965), is no longer anything like the film.

O’Donnell found more satisfaction in writing the novels. In writing the strip, he produced crudely drawn thumbnails of the panels so he would know how much space the words were taking—and, conversely, that sufficient room remained for the artwork. But the novels were solo performances with the writer in complete control. Moreover, in a novel “there’s elbow room to give more nuances of feeling and to say what’s going on inside your characters.”

The novels also more fully explain the relationship between Modesty and Willie, supplying an answer to the question O’Donnell has been plagued with more than any other.

From the novel Sabre-tooth: “Modesty … by some strange magic had stripped away the veneer and liberated Willie Garvin from the gnawing demons who rode on his back. For this liberation, the new Willie Garvin had made himself—not her slave, for she would not allow that, but her eternally faithful follower. And though she had raised him up to become her right arm, he still sat at her feet. And there was no loss of masculinity in this…. Willie Garvin was wholly convinced that sitting at Modesty’s feet set him head and shoulders above any man alive—even those few who had known the gifts of her splendid body.”

To suggest, as some did, that there was something sexual between them embarrassed Willie “as a devout believer might be embarrassed by a friend’s unwitting sacrilege.”

Said O’Donnell: “It’s a relationship women understand better than men.”

By 1973, Modesty Blaise was published in 76 newspapers in 35 countries. The strip appeared in the U.S. in 30-40 papers at the time the Losey movie ran. All but the Detroit Free Press soon dropped it, saying the stories ran too long, 16-17 weeks. U.S. papers wanted O’Donnell to cut back to 12 weeks, but he refused. To do so, he said, would cut the meat out. “You’ll end up with no depth of character, no humor, none of the fleshing out and asides that, to my mind, are vital parts of the success of the Modesty Blaise/Willie Garvin setup.”

O’Donnell and Holdaway met once a week when the artist delivered the week’s worth of strips to the writer at his Fleet Street office. O’Donnell would look over the strips, and if “amendments” were needed, Holdaway would make them. And then they would deliver the completed batch across the street to the Standard offices.

Writing later of these encounters, O’Donnell said he never knew quite what to expect on the day Holdaway was to appear. “Sometimes the door would open an inch, and a voice would order me to throw out my gun and come out with my hands up. Sometimes he was the gas-meter man with a falsetto voice. Sometimes his hat would be thrown in, and sometimes the first I knew of his arrival was when clouds of cigarette smoke would come wafting through my old-fashioned office letter-box…”

They worked well together, O’Donnell believed. “We enjoyed and respected each other’s contribution and worked together in the greatest harmony.”

Then in 1970, in the midst of their 18th Modesty story together, the great Jim Holdaway died. Struck down by a wholly unexpected heart attack at the youthful age of 43. Fifteen years after Holdaway’s death, O’Donnell would write: “Jim Holdaway was a small man with a gentle manner, an immense talent, and a lovely sense of humor. I still miss him.”

The Standard editors held try-outs for a replacement, and they and O’Donnell finally settled on a Spaniard, Enrique Badia-Romero. Thereafter, the production of the strip was conducted mostly by mail, which made a detour at the Standard offices for O’Donnell’s scripts to be translated into Spanish.

Romero left Modesty in 1978 to concentrate on a strip of his own, Axa. He returned in the fall of 1986 and continued to draw the strip for the rest of its run. During his sabbatical, Modesty was drawn briefly by John Burns, then Pat Wright, and, finally, Neville Colvin from late 1980 until Romero’s return, a total of 15 stories. Colvin’s work seemed to O’Donnell to be closer to Holdaway’s than any of the other successors; and I agree although he was closer at the beginning than at the end of his tour. Colvin applied more feathering and fragile-line shading than the others, and his Modesty was more glamorous.

In the early 1970s, O’Donnell began writing another series of novels—these, all under the name Madeleine Brent. Nine altogether, they each feature a different female protagonist telling the story in the first person. Set in the late Victorian era in England, part of each story takes place elsewhere—China, Australia, Afghanistan, Mexico.

Said O’Donnell: “I think that people who like my Modesty books will like these as well. They have the same kind of adventure in them.”

One of the novels, Merlin’s Keep, in 1978 won the Romantic Novel of the Year Award from the Romantic Novelists’ Association.

All 95 of the Modesty Blaise stories (and the 12 back-story strips about Modesty’s refugee life) have been reprinted in one place or another. Titan Books in England published 23 stories in eight 9×11″ paperbacks which present the highest quality reprints, nearly pristine reproduction of every line no matter how fragile. Ken Pierce of Illinois published another 21 stories (only three of which duplicate Titan’s) in eight 7″x10″ paperbacks. The quality here, too, is virtually perfect but the strips are smaller than in the Titan volumes. All of Holdaway’s work can be found in either Titan or Pierce.

The rest of the canon has been published by Comics Revue, sometimes in special Modesty Blaise issues that contain whole stories, sometimes serialized in the regular monthly magazine. The quality of reproduction here, however, is very uneven—due, doubtless, to the source material, which, apparently, is not always printer’s proofs.

Modesty Blaise was one of the last great adventure strips, and it is arguably the most literate adventure strip ever. And the novels are better than the strip. The books have an advantage over newspapers’ serial mode: their emotional content is cumulative not diffused over intervening days and therefore builds toward greater impact.

Modesty Blaise was one of the last great adventure strips, and it is arguably the most literate adventure strip ever. And the novels are better than the strip. The books have an advantage over newspapers’ serial mode: their emotional content is cumulative not diffused over intervening days and therefore builds toward greater impact.

In the last of the books, the short story collection The Cobra Trap, O’Donnell arranged the retirement of his dauntless pair. They die. They die gracefully, in battle, as befits such legendary soldiers of fortune. O’Donnell brings down the curtain with his usual finesse, easing Willie into the afterlife on the last page of the title story.

This tale takes place 20 years “in the future,” so Modesty and Willie are in their fifties. In the final newspaper comic strip story, “The Zombie,” they are still in their thirties and have twenty more years of exploits before them.

At the end of the last strip adventure, Modesty announces that she is tired of villains and secret service work and wants to do something “crazy—just for fun. We’ll take a little break, Willie love,” she says, “just you and me.” Says he: “Best bit of all, Princess.” And they sail off in a yacht.

The strip ended April 11, 2001. It was O’Donnell’s 81st birthday. He would die nine years later at the age of 90. He suffered from Parkinson’s in his later years.

- Funnies Farrago Celebrates a Half Century of Doonesbury - June 1, 2022

- Who Really Invented the Comic Character ‘Archie’? - May 7, 2022

- Dick Wright Returns - April 5, 2022