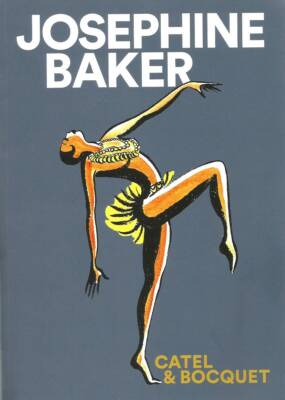

An exemplary graphic novelistic biography on Josephine Baker.

Funnies Farrago: a Column on Comics and Cartooning

Written by Jose-Louis Bocquet and drawn by Catel Muller, Josephine Baker is 570 6×9-inch pages in b/w from SelfMadeHero in 2017 paperback. It is more vividly described as an-inch-and-a-half thick, weighing two-and-a-half pounds. A doorstopper of a book.

It is also an excellent model of a comicbook-style biography. Or graphic novel.

Bocquet and Muller successfully exploit the medium to tell the story of this African American entertainer who became a sensation in Paris in the 1920s by dancing almost nude and who then joined the French resistance during World War II and, after the war, deployed her fame to advocate for civil rights and racial justice, and, to prove a point, adopted and raised 12 children from different cultural and racial backgrounds.

Bocquet and Muller successfully exploit the medium to tell the story of this African American entertainer who became a sensation in Paris in the 1920s by dancing almost nude and who then joined the French resistance during World War II and, after the war, deployed her fame to advocate for civil rights and racial justice, and, to prove a point, adopted and raised 12 children from different cultural and racial backgrounds.

The book is successful as biography and as graphic novel form because it presents Baker’s life as a series of incidents and episodes, dramatizing the highlights and key moments of her life and career in picture and words. Each of the episodes is a story: each has a beginning, middle, and end. And the characters being depicted talk and act—like comicbook characters everywhere. They’re not just talking heads.

Many other biographies in the graphic novel genre fail because they are only illustrated prose narratives. Or pictorially decorated prose narratives. (And the prose is not very good.) In properly exploiting the form, Bocquet and Muller add drama and energetic life to the story of Josephine Baker.

Baker was born in St. Louis in 1906 and died in Paris in 1975. An African American, she gained fame in the 1920s as an exotic dancer in Paris: headlining revues at the Folies Bergere, she danced nearly naked, saith St. Wikipedia, famously wearing only a short skirt of fake bananas and a beaded necklace.

Baker was celebrated by artists and intellectuals of the era, who variously dubbed her the Black Venus, the Black Pearl, the Bronze Venus and the Creole Goddess. She renounced her U.S. citizenship and became a French national after her marriage to French industrialist Jean Lion in 1937. It was her third marriage, and until her fourth, none lasted longer than a year or so.

Baker aided the French Resistance during World War II. When the Germans invaded France, Baker left Paris and went to the Château des Milandes, her castle in the south of France. There, she housed people who were eager to help the Free French effort led by de Gaulle and supplied them with visas. As an entertainer, Baker had an excuse for moving around Europe, visiting neutral nations such as Portugal, as well as some in South America. She carried information for transmission to England—about airfields, harbors, and German troop concentrations in the West of France.

After the war, she was awarded Croix de guerre by the French military, and was named a Chevalier of the Légion d’honneur by General Charles de Gaulle.

She made occasional visits to the U.S. but refused to perform for segregated audiences and is noted for her contributions to the civil rights movement. In 1968 she was offered unofficial leadership in the movement in the United States by Coretta Scott King, following Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination. After thinking it over, Baker declined the offer out of concern for the welfare of her children.

During Baker’s work with the civil rights movement, she began adopting children and forming a family (two girls and ten boys) that she often referred to as “The Rainbow Tribe.” Baker wanted to prove that “children of different ethnicities and religions could still be brothers.”

In 1949, a reinvented Baker returned in triumph to the Folies Bergere. Bolstered by recognition of her wartime heroics, Baker the performer assumed a new gravitas, unafraid to take on serious music or subject matter. The engagement was a rousing success and reestablished Baker as one of Paris’ preeminent entertainers. In 1951 Baker was invited back to the United States for a nightclub engagement in Miami. After winning a public battle to desegregate the club’s audience, Baker followed up her sold-out run at the club with a national tour.

Baker worked with the NAACP. Her reputation as a crusader grew to such an extent that the NAACP had Sunday, May 20, 1951 declared “Josephine Baker Day”. She was presented with life membership with the NAACP by Nobel Peace Prize winner Dr. Ralph Bunche.

Among her more famous utterances is what she said at the March on Washington, August 28, 1963. Martin Luther King’s “dream speech” is the better remembered, but Baker’s is notable for its blunt assertion of the cause of civil rights:

“I have walked into the palaces of kings and queens and into the houses of presidents. And much more. But I could not walk into a hotel in America and get a cup of coffee, and that made me mad. And when I get mad, you know that I open my big mouth. And then look out, ’cause when Josephine opens her mouth, they hear it all over the world …”

Above, I’ve posted pages from the book that exemplify Bocquet and Muller’s manner of storytelling.

The verbal-visual narrative of Baker’s life ends with her funeral on pages 459-460. Then follows a 16-page “timeline” that tells the story of Baker’s life in straight chronological prose. That is followed by an 83-page section of one-page mini-biographies of the people in Baker’s story—her husbands and various celebrities, Eubie Blake, Ernest Hemingway, Georges Simenon, Colette, Le Corbusier, Charles de Gaulle, Grace Kelly and many others—and a bibliography.

The verbal-visual narrative of Baker’s life ends with her funeral on pages 459-460. Then follows a 16-page “timeline” that tells the story of Baker’s life in straight chronological prose. That is followed by an 83-page section of one-page mini-biographies of the people in Baker’s story—her husbands and various celebrities, Eubie Blake, Ernest Hemingway, Georges Simenon, Colette, Le Corbusier, Charles de Gaulle, Grace Kelly and many others—and a bibliography.

But it’s the preceding 460 pages that make this book an exemplar in its form. Anyone who aspires to produce a biography in graphic novel form is hereby urged to read this Josephine Baker as a guide to how such books should be done.

- Funnies Farrago Celebrates a Half Century of Doonesbury - June 1, 2022

- Who Really Invented the Comic Character ‘Archie’? - May 7, 2022

- Dick Wright Returns - April 5, 2022