Funnies Farrago presents: Morrill Goddard, Godfather of the “Comics”

Morrill Goddard is not a name we readily associate with the comics. In fact, it is a name that crops up only occasionally in histories of American newspapers and in biographies of some of the press barons who built their fiefdoms on the work of journalists like Goddard. And wherever his name appears, it never gets more than a paragraph. Sometimes, only a sentence. Goddard is nearly unknown because the man had a passion for anonymity. All that we know about him is divulged herewith—in connection with what we have been calling “comics” for generations.

But the “comics” are not necessarily comical, the obvious meaning of the word to the contrary notwithstanding. Bugs Bunny, Batman, Dagwood, Mary Worth. Whether in pulpy pamphlets or newspapers, comics are sometimes funny and sometimes quite serious. So why call them “comics”? The reasons for the anomaly are evident in the history of the medium, a history over which Goddard hovers consequentially albeit largely unacknowledged.

But the “comics” are not necessarily comical, the obvious meaning of the word to the contrary notwithstanding. Bugs Bunny, Batman, Dagwood, Mary Worth. Whether in pulpy pamphlets or newspapers, comics are sometimes funny and sometimes quite serious. So why call them “comics”? The reasons for the anomaly are evident in the history of the medium, a history over which Goddard hovers consequentially albeit largely unacknowledged.

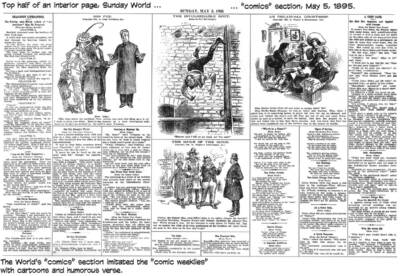

Newspapers had published cartoons before 1893, but it was in the spring of that year that the New York World started publishing cartoons in a Sunday supplement that became embroiled in a circulation war in the Big Apple, which, taking place in the nation’s largest city where the media set a pace for the rest of the country, had ramifications beyond the city limits.

Morrill Goddard, an intense man with exacting journalistic standards, was the editor of the Sunday World. At the time of his death in July 1937, his assistant of 26 years, Abraham Merritt, wrote a elegiac obituary in Editor & Publisher (July), confessing that soon after he started working for Goddard, he began to think his boss was the greatest of editors. “There might have been some hero worship in it then,” he admitted, “but now, after a quarter of a century, I no longer think he was the greatest editor of his day. I know he was.”

Goddard “abhorred all sham and pretense,” Merritt wrote. “He took a grim joy in pricking the balloon of some inflated personality. He had a passion for accuracy … [He was] a constant challenger of what he considered ‘mischievous fallacies’” masquerading as truths or facts. Goddard, Merritt went on, “combined in one extraordinary synthesis creative and executive genius of the highest order. He had the unique power of being able to project himself into the minds of all classes of people, discover and be interested in what interested them and reflect that interest in the pages of his paper.”

Devoted single-mindedly to his profession, Goddard was essentially defined by his dedication. His was a simple, unprepossessing personality. “I know of no man,” Merritt said, “who, occupying the position he did, being what he was, had so little egotism, who was so devoid of what he called ‘high hat bunk.’”

In his personal conduct, demanding though he was of subordinates and reporters, Morrill Goddard was deliberately self-effacing and was virtually unknown by the public at large. He never had a photograph taken. “Once,” Merritt said, “when I inadvertently snapped [a photo of] him while on one of his boats, he made me destroy the film. ‘Nobody is interested in me,’ he’d say. ‘All they’re interested in is my product.’”

His product for most of his long life was the newspaper Sunday supplement that he edited at William Randolph Hearst’s American Journal. “It was,” Merritt asserted, “the main and almost the only interest in his life.” But Goddard had a life before Hearst. Hearst had found him at Joseph Pulitzer’s New York World, where, on May 21, 1893, Goddard had produced the first Sunday comics supplement in color.

The idea of a color Sunday “magazine” had been under discussion at the World since 1891, according to Roy L. McCardell, who wrote about it in Everybody’s Magazine for June 1905. The paper started a comics section in 1889, but it wasn’t until 1893 that a press was devised that could print color accurately. At first, the paper’s editors thought the color supplement should be devoted to women’s fashions, “but just about that time, Goddard, city editor of the World, was made Sunday editor.” And Goddard “was emphatically against the fashion supplement.”

Morrill Goddard “went in for the weird and wonderful in everyday life,” said McCardell, “and if things were not so weird and wonderful enough for him, he made them so.”

In his Pulitzer: A Life, Denis Brian retails several stories about Goddard’s inventive circulation-building enterprise: “Dartmouth graduate Goddard … persuaded a leading Episcopal clergyman to live in a Hell’s Kitchen tenement for six weeks and report his impressions, which started with a sizzling: ‘I would rather live in hell than Hell’s Kitchen.’ …

“Considered the leading practitioner of the ‘crime, underwear and pseudo-science school of journalism, Goddard illustrated a science feature on anatomy with the shapely legs of actresses and showgirls.’” On another occasion, Goddard concocted “a hilarious account of a raunchy stag party thrown by architect Stanford White, in which, for dessert, a naked model ‘covered only by the ceiling,’ as the World put it, stepped from a papier-mâché pie. … Goddard had spread an eye-catching sketch of the shapely dessert across two pages.”

In a widely available history of journalism, The Press in America, Edwin Emery observes that Morrill Goddard “jazzed up his page spreads, exaggerating and popularizing the factual information. Scientists particularly were the victims of the Sunday newspaper’s predilection for distortion and sensationalism, and the pseudo scientific stories of yellow journalism made the men of science shy away from newspaper coverage for the next 50 years.”

In an article, “The Fourth Current,” in Collier’s (February 18, 1911), one of Goddard’s staff explained the operation:

“Suppose it’s Halley’s comet. Well, first you have a half-page of decoration showing the comet, with historical pictures of previous appearances thrown in. If you can work a pretty girl into the decoration, so much the better. If not, get some good nightmare idea like the inhabitants of Mars watching it pass. Then we want a quarter of a page of big-type heads—snappy. Then four inches of story, written right off the bat. Then a picture of Professor Halley down here and another of Professor Lowell up there, and a two-column boxed freak containing a scientific opinion, which nobody will understand, just to give it class.”

And it was Morrill Goddard’s “professional opinion,” McCardell avowed, “that American humor, not fashion, ought to have a colored pictorial outlet.” To give the World class, we might say.

Goddard’s plan for the World’s color Sunday supplement was to make it in the image of the weekly humor magazines of cartoons and humorous verse then enjoying enthusiastic readership in New York and around the country. At first, Goddard was forced to reprint cartoons from the humor magazines because many of the most desirable cartoonists were under contract with them and obliged to give them first refusal rights.

At the time, McCardell was on the staff of one of them, Puck, and Goddard, in quest of work that would be original with the World, approached him, asking if he knew any artists who could do comic work who were not contracted to any of the weeklies. McCardell directed Goddard to Richard F. Outcault, a draftsman on the staff of the Electrical World and the Street Railway Journal, who had been dabbling in comic pictures, too. Outcault would do his first original work for the World with a comic strip published September 16, 1894. He would eventually produce a half-page comical drawing called “Hogan’s Alley” in which a bald-headed kid in a yellow nightshirt stood out among the other street urchins and, as “the Yellow Kid,” would demonstrate and establish the commercial value of comics to newspapers by boosting circulation, thus assuring the subsequent maturation of the comic strip form. Meanwhile, Outcault continued doing cartoons for Truth, one of several humorous weeklies in the mold of Puck, Judge and Life, the three most popular of the genre.

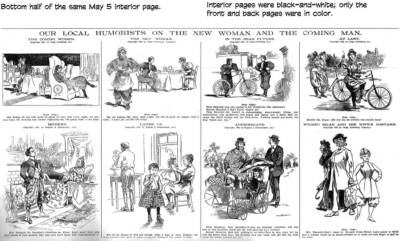

Offering comical drawings and amusing short essays and droll verse, these magazines were dubbed “comic weeklies” in common parlance—or, even, “comics.” So when the World launched its imitation “comic weekly” as a supplement to its Sunday edition, it was lumped together in the popular mind as another of the “comics.”

In short, “comics” denoted the vehicle not the art form.

And then, once the World had shown the way, papers in other cities began publishing humorous Sunday supplements full of funny drawings in color and risible essays and verse. In a relatively short time, obeying the dictates of demand, newspapers eliminated the essays and verse and concentrated on comical artwork, which was increasingly presented in the form of “strips” of pictures portraying hilarities in narrative sequence. It was but a short step to the use of comics to designate the art form (cartoons and comic strips) as distinct from the vehicle in which they appeared (the Sunday supplement itself). Once that bridge was crossed, meaning deteriorated pretty rapidly.

Storytelling (or “continuity”) strips arrived in the 1920s, and even when, in the 1930s, the stories they told were serious, they were called “comics” because they looked like the art form called comics and they appeared in newspapers with all the others of that ilk. Finally, when comic strips began to be reprinted in magazine form in the 1930s, the now-generic term was applied to those magazines, too; in the new format, comic books quickly emerged from comics (although the latter persisted as an alternative name for the former).

Disputation about where the first newspaper comics appeared and who drew the first ones has fomented for years. Was it the New York World or, as it has lately be asserted, the Inter Ocean in Chicago that published the first Sunday color comics? Was Outcault the first with a regularly appearing comics feature? Or was it Charles Saalburg with The Ting Lings in the Inter Ocean?

Wherever and whoever will eventually emerge undisputed with the titles, the World seems both judicious and accurate in its editorial published in 1928 when Outcault died:

“To say that the late R.F. Outcault was the inventor of the comic supplement [a generous but erroneous attribution of early comics history] is of course to ignore the social factors that lead up to all inventions. … But it is due Morrill Goddard … to say that he saw in the early nineties that the time was ripe for ‘comic art,’ and it is due Mr. Outcault to say that his talent made the most of the opening” (quoted in A History of American Graphic Humor, Vol. 1: 1865-1938 [136] by William Murrell).

Whether the evolution of the term followed the lines I’ve sketched precisely or only generally (the Oxford English Dictionary is not explicit in its etymology), it is certain that a confusing coinage was in wide circulation. And it is also certain that we call the art form “comics” rather than the less confusing “cartoon strips” or (for comic books) “paginated cartoon strips” because of Goddard’s inspired deployment of the World’s Sunday supplement as an imitation of weekly humor magazines.

- Funnies Farrago Celebrates a Half Century of Doonesbury - June 1, 2022

- Who Really Invented the Comic Character ‘Archie’? - May 7, 2022

- Dick Wright Returns - April 5, 2022