Jackie Ormes: The first professional black woman cartoonist in the U.S.

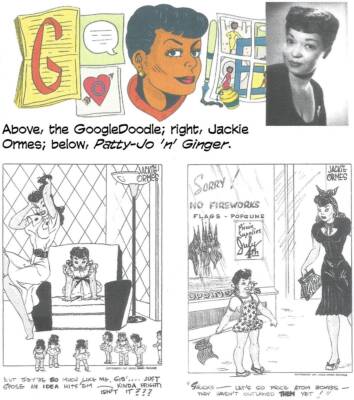

Google has a Doodle every day. I didn’t know this. A Google Doodle, it sez here, is a special, temporary alteration of the logo on Google’s homepages intended to commemorate holidays, events, achievements, and notable historical figures. Google got September off to a good start by highlighting a cartoonist in its Doodle for September 1. Not only was the Doodle about a cartoonist, it was also drawn by a cartoonist. And both cartoonists are women. And both women are Black!

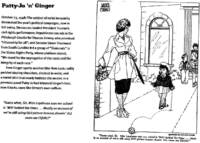

The occasion that prompted this happy coincidental, said Sarah Cascone at artnet.com, is the 75th anniversary of Jackie Ormes’ longest-running cartoon, Patty-Jo ‘n’ Ginger, first published on September 1, 1945. The single-panel cartoon, which featured the precocious insight of Ginger’s young sister Patty-Jo, ran for 11 years and inspired an unusual toy doll from Terri Lee: it was the first American Black doll to have an extensive line of clothes, and it eschewed common racial stereotypes.

The occasion that prompted this happy coincidental, said Sarah Cascone at artnet.com, is the 75th anniversary of Jackie Ormes’ longest-running cartoon, Patty-Jo ‘n’ Ginger, first published on September 1, 1945. The single-panel cartoon, which featured the precocious insight of Ginger’s young sister Patty-Jo, ran for 11 years and inspired an unusual toy doll from Terri Lee: it was the first American Black doll to have an extensive line of clothes, and it eschewed common racial stereotypes.

Patty-Joe gets all the good lines in the cartoon, including a few scathing comments on the evil of racism. Ormes also did a Sunday comic strip, Torchy Brown in Heartbeats, which ran for many of the same years Patty-Jo ‘n’ Ginger ran.

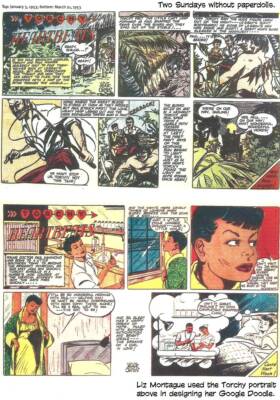

To design its homepage Google Doodle tribute to Ormes, Google tapped Philadelphia-based artist Liz Montague (who probably is the first Black woman cartoonist to make it into prestigious The New Yorker; no one can say for sure because the race and other identities of a New Yorker cartoonist is not systematically solicited by the magazine or recorded anywhere. But no one today remembers seeing any Black women cartoonists around in years past.)

“I drew a lot of inspiration from Jackie’s illustration style, such as the lines she uses as well as her compositions and layouts,” Montague told Google.

“Jackie is a huge inspiration for me… The illustrations are immaculate, the humor is witty, the social criticism is bitingly accurate—her work is just the total package. She is why I create cartoons as social justice and why I feel valid doing it. Jackie is a genius and paved the way for so many of us as a pioneer in the cartoon and illustration world.” …

“Her work was unique and wholly unprecedented. Not only were her lead characters female, they were strong, elegant, intelligent, urbane, opinionated, and witty and often leading extremely glamorous and cultured lives,” Josphine Liptrott wrote of Ormes in a brief online biography for the Heroine Collective. “They challenged the derogatory caricatures of Black people, and especially Black women, which usually appeared in comics at that time.”

For more about Jackie Ormes, we can consult a book-length biography, Jackie Ormes: The First African American Woman Cartoonist (264 8.5×11-inch pages, some in color; U. of Mich. Press 2008 hardcover, $35) by Nancy Goldstein.

Ormes (1911-1985), whose maiden name was Zelda Mavin Jackson, was dubbed “Jackie” early in life, an invocation of her last name by relatives of the stepfather she acquired when her mother married again following the death, in an auto accident, of her biological father, William Winfield Jackson. And when in 1931 Jackie married Earl Clark Ormes, a man seven years her senior, the neophyte cartoonist’s re-christening was complete. When Earl died 45 years later, they were still married, but by then, Jackie had worked in weekly African American newspapers, starting at the Pittsburgh Courier and then at the Chicago Defender, as a reporter and writer. And she had also produced a string of cartoon features, to wit—:

May 1, 1937 – April 30, 1938: Torchy Brown in Dixie to Harlem, a weekly comic strip in daily format

March 24 – July 21, 1945: Candy, a panel cartoon about a wise-cracking housemaid

September 1, 1945 – September 22, 1956: Patty-Jo ‘n’ Ginger, another panel cartoon, her longest running

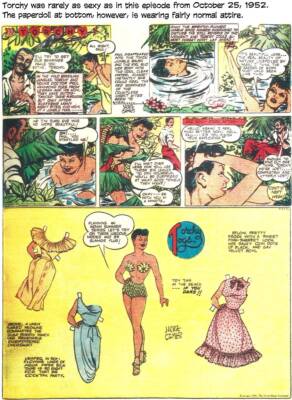

August 19, 1950 – September 18, 1954: Torchy returns in Torchy Brown in Heartbeats, a Sunday adventure comic strip in color

The latter was often accompanied by Torchy’s Togs, a half-page panel in which Torchy appeared as a paper-doll with an impressive wardrobe clustered around her, demurely attired in her undies or a swimsuit—she was, in short, a pin-up (and she bore a remarkable resemblance to her diminutive creator).

The Pittsburgh Courier, for which Ormes produced her most remembered cartoon features, had fourteen regional editions, and the Pittsburgh edition distributed Patty-Jo ‘n’ Ginger and Torchy to all of them. In other words, Ormes was syndicated nationally albeit not on the scale of, say, King Features. Ormes was, Liptrott says, “the only Black female cartoonist to have been syndicated in the U.S. until the 1990s.”

Most Black newspapers of the time were vehicles of social uplift, dedicated to championing Black citizens’ causes and advocating their interests, and Ormes’ cartooning was devoted to the same project.

“The newspaper industry of mid-20th century America offered precious few opportunities for women, still less for women of color,” Liptrott observed. “This made Jackie Ormes’ achievement as a successful Black female cartoonist all the more remarkable.

“Her work was unique and wholly unprecedented,” Liptrott went on. “Not only were her lead characters female, they were strong, elegant, intelligent, urbane, opinionated and witty and often leading extremely glamorous and cultured lives.”

The Goldstein Ormes biography, to which the author was prompted by her interest in dolls, becoming diverted when she learned that the first “Negro” doll, Ormes’ Patty-Jo, was based upon the cartoon character, is the shortest part of the book—about 90 pages of text, plus a 23-page chapter about Jackie’s doll-making career.

Most of the remainder of the volume reprints healthy samples of Ormes’ panel cartoons and strips, many not seen since their initial publication in Black newspapers—enough of each that, for the first time, we have a good idea of just how, for instance, Torchy Brown’s 1950s incarnation was different than her initial appearance in the 1930s. The latter was a humorous continuity about a small-town girl venturing into the big city; the former, a serious adventure strip, in which Torchy is menaced more than once by would-be rapists.

Unhappily, the reproduction of Ormes’ work is sometimes problematic: Goldstein had to use microfilm for the Dixie strips, Candy, and many of the Patty-Jo panels, but she also found 25 Patt-Jo originals and included those.

Heartbeats, reproduced from tearsheets, is all in color, 19 pages of it, the longest stretch I’ve ever seen of the strip for which Jackie Ormes is most remembered.

But it was in Patty-Jo and Ginger that the cartoonist often took a stand on many of the controversial political and cultural issues of the day, speaking openly and critically about racism, the arms build-up, and current foreign policy and in favor of voter awareness and feminist concerns—“stuff hardly seen in the mainstream newspapers,” Goldstein notes, “all done by a Black woman.”

Although Jackie was fair-skinned enough to pass for white, she was much too dedicated to African American causes to abandon her birthright.

The section reprinting Patty-Jo and Ginger is the longest in the book, 44 pages with two cartoons to a page, each extensively annotated by Goldstein, who explains the social and political context of the comedy. Having never beheld this feature before, I was intrigued by its unusual rhetoric.

Patty-Jo, a girl of about 8 or 9, gets all the lines, often speaking out against racism or some other societal hang-up, while her older sister, Ginger, a statuesque beauty, never talks at all: she is just there, standing or posturing in ways that display her admirable figure or her high fashion frocks. Ginger, in other words, is a pin-up, Ormes’ canny come-on that seduced readers, female (for the fashions) as well as male (for the sex appeal), so Patty-Jo could lay short socially conscious sermons on them.

So successful was Jackie at this maneuver and so outspoken on liberal issues such as racial equity and the folly of American foreign policy both in the cartoon and in activist organizations that she was investigated by Edgar Hoover’s FBI, and Goldstein presents the evidence: one of the appendices of the book consists of excerpts from Ormes’ FBI file, including paraphrases of Jackie’s testimony when questioned about her involvement with so-called Communist front groups:

“Ormes pointed out that being a member of a minority group and a liberal she could clearly see where she might be misled by the programs of front groups without necessarily seeing the underlying objectives of such organizations.”

She also said she thought the Communist movement was somewhat innocuous, “constituting no apparent threat to the continued existence of this country’s form of Government.”

Although Jackie Ormes worked in daily journalism, she was a member of the elite Black social set in Chicago for most of her adult life. Her childhood was spent in Monongahela, Pennsylvania, and she lived and worked for seven years in Pittsburgh, but she moved to the Windy City in 1938, when the “Chicago Renaissance” in Black culture was surfacing in the wake of the dissipating “Harlem Renaissance” in New York.

Bronzeville, South Side Chicago, reportedly was “the largest Negro city in the world” after Harlem. Jackie’s husband had started in banking in Pittsburgh, but the Depression elbowed him out of that occupation, and in Chicago, he became manager of the DuSable Hotel, known for its Black celebrity clientele. After ten years there, he took a similar position at the Sutherland Hotel, one of the classiest in the area, where all the visiting Black dignitaries bunked when in town.

In Pittsburgh, Jackie numbered Lena Horne and Billy Eckstine among her friends; in Chicago, possibly Duke Ellington and Count Basie. Her feisty demeanor and professional success in almost every endeavor masked a tragedy Jackie suffered early in life when her only child, a daughter named Jacqueline, died in 1936. Goldstein writes:

“Treatments for childhood cancers were not advanced in the 1930s, and at the age of three-and-a-half, Jacqueline died while cradled in her mother’s arms. According to her sister Delores, Jackie was determined not to bear more children or to go through heartache like that again. She was always to keep her sorrow to herself, never speaking about Jacqueline, except once to tell Delores, ‘I will never lose my empty arms.’”

Despite its seeming brevity, this book is excellent, a revealing and thoroughly documented glimpse into African American life of the times, the racist mores of the era, and the professional and personal life of a little-known but oft-celebrated figure in the history of American cartooning. Goldstein is scholarly without being pedantic, performing extensive research into the existing record of Ormes’ oeuvre and interviewing the cartoonist’s surviving relatives, who, upon learning of Goldstein’s interest, shared family stories, newspaper clippings, and photographs.

Despite its seeming brevity, this book is excellent, a revealing and thoroughly documented glimpse into African American life of the times, the racist mores of the era, and the professional and personal life of a little-known but oft-celebrated figure in the history of American cartooning. Goldstein is scholarly without being pedantic, performing extensive research into the existing record of Ormes’ oeuvre and interviewing the cartoonist’s surviving relatives, who, upon learning of Goldstein’s interest, shared family stories, newspaper clippings, and photographs.

“At a time when America’s media depicted the Black population in a generally derogatory way, Jackie Ormes challenged the status quo, flouted the stereotypes and provided bright and brilliant role models in her work,” said Liptrott. “She was an inspiration, a trailblazer and an incredible agent of change.”

And Goldstein’s book, in bringing to light the work and achievements of this Black female cartoonist, supplies the reasons for Liptrott’s assessment.

- Funnies Farrago Celebrates a Half Century of Doonesbury - June 1, 2022

- Who Really Invented the Comic Character ‘Archie’? - May 7, 2022

- Dick Wright Returns - April 5, 2022