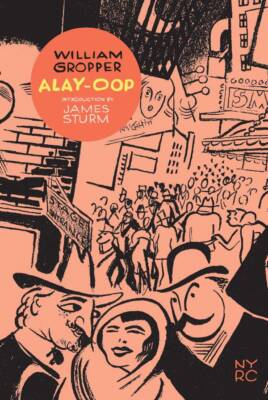

The title of “Alay-Oop,” a graphic novel by William Gropper, comes from the French “allez-houp!” the cry of an acrobat about to leap (“Let’s go! Up!”).

I’VE ALWAYS WONDERED about William Gropper. His name crops up here and there without much amplification.

Who was he? And why? Maybe I’m just obtuse and have overlooked revealing clues on all sides. Maybe not. Then last summer, a book appeared — a graphic novel by Gropper with an Introduction by James Sturm, co-founder of the Center for Cartoon Studies in White River Junction, Vermont (and the founder of the National Association of Comics Art Educators, an organization committed to helping facilitate the teaching of comics in higher education) — and the person likely responsible for re-issuing the book. Entitled Alay-Oop, the novel runs 210 5.5×8-inch pages, b/w (New York Review Comic, hardcover, $24.95).

The book’s title comes from the French “allez-houp!” the cry of an acrobat about to leap (“Let’s go! Up!”). The title is the book’s only words. The wordless story involves vaudeville acrobats, a man and a woman, who are friends with another theatrical act, an opera singer, who admires the woman. The three often go dining together, and the opera singer regales them (the woman particularly) with his stories. One night, the woman dreams a dream about a woman, herself perhaps, and a stallion. The next day, she is visited by the opera singer, who shows her his bank book and tells her (via speech balloon pictures) about what a grand life is possible. He concludes by offering her an engagement ring. Right away, she marries the singer, and she and her acrobatic partner terminate their engagement at the theater.

The three maintain a friendly relationship, and years later, after the woman has given birth to twins, her acrobatic partner shows up to entertain the kids while their mother washes clothes, irons, cooks, and so on. The singer, the kids’ father, is still telling stories about great wealth in the future. But there’s nothing in the present. He grows jealous as he sees that his kids worship the acrobat visitor. He even wonders if the acrobat isn’t secretly the father of the twins.

Then the acrobat begins training the twins to do simple tricks, and when they become quite accomplished, he suggests to their mother, his former partner, that they develop an act for the four of them. Once when they are rehearsing, the singer comes home and sees them doing a trick. He orders the acrobat to leave and begins berating his wife. His tirades grow so furious and unending that she leaves him, taking the twins with her. The singer, having wrecked their apartment in one of his rages, slinks off.

Years later, he has found employment selling fruit from a horse-drawn wagon — singing about his wares to attract customers. The male acrobat now flies high as a steelworker on the girders of skyscrapers. And the woman is in the circus with her twin daughters, working with trick horses.

Sturm says he wishes Gropper had done more graphic novels. “For here was an artist in total command of his craft, in the prime of his career, directing his energies toward an art form whose potential was just beginning to be tapped.”

He bought his copy of Alay-Oop for $100. “It was the most I had ever spent on a book, but I had to have it. Part of its appeal was that it was a historical novelty (a graphic novel before the term existed!) but it was far more than that: it told a very human story with style and verve. In any era, that is a rare and beautiful thing.”

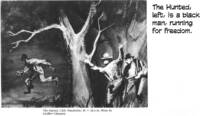

Originally published in 1930, Gropper’s tale is one of several wordless books of narrative illustrations that appeared about then, inspired by Frans Masereel, a Belgian, who would produce over 50 wordless books of woodcut pictures. His first, in 1918, offers a criticism of “the growing power and wealth of industrialists at the expense of a population of workers living in squalor,” as David Berona puts it in his survey, Wordless Books: The Original Graphic Novels (Abrams 2008). Masereell’s second woodcut novel, Passionate Journey (1919), is “perhaps the seminal work in the genre,” saith Berona.

Lynd Ward, an American, saw Masereel’s 1919 The Sun while studying in Germany in 1926, and subsequently produced his first wordless woodcut novel, God’s Man, in 1929. About the same time, cartoonist Milt Gross did a wordless novel, He Done Her Wrong (1930).

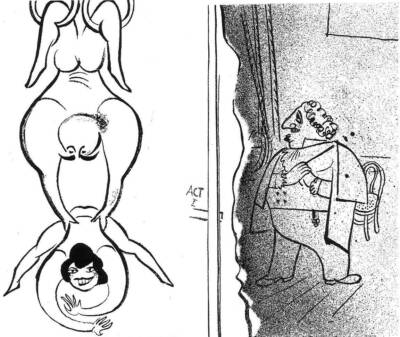

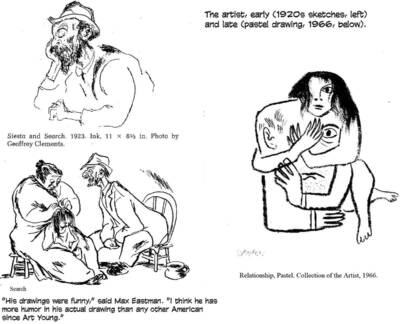

Inspired, doubtless (while Gross was then working on a screen play in Hollywood), by the melodrama of silent adventure films, the book is an outright lampoon of the genre — and of Ward’s pretentious oeuvre — but drawn in the much simpler style of a cartoonist rather than an illustrator. Moreover, Gross’s book is humorous; Ward and Masereel’s books are grimly serious. William Gropper takes a step in the same direction of simplification as Gross: some of his drawings are nearly abstractions.

Neither Gross nor Gropper produced any other graphic novels, wordless or wordy. But Gropper’s book prompted me to find out more about him. He eventually took his cartooning talent into painting and illustration and became famous at each endeavor, and everywhere his radical socialist views persisted. St. Wikipedia calls William Gropper a painter, lithographer, and muralist, but his first love was cartooning, and most of his work in other genre looks much like colored cartoons.

And I wonder now, having researched him for this essay, why we who love cartooning in all its aspects have heard so little about Gropper, who, as one of my sources observed, “is unique among artists in America” in having so resounding a success in his double profession, painter and cartoonist.

BORN IN NEW YORK CITY in 1897 to immigrant parents, he grew up on the Lower East Side in poverty: his father, university-educated and fluent in eight languages, could find no work in a field for which he was suited and was forced to accept manual labor, and whenever he found a job, he had difficulty holding it. This failure of the American system to make proper use of his father’s talents probably soured William’s attitude about capitalism, and when a favorite aunt died in the infamous Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire on March 25, 1911, his antipathy was completed. (In the fire, 146 people died because they could not escape from their work places on the 8th, 9th and 10th floors of the building: the doors were all locked to prevent workers from taking unauthorized breaks and to reduce theft. Many of those who died leapt to their death from the burning factory floors.)

In a biographical essay in his book William Gropper (1983), Louis Lozowick, a painter and critic, says the neighborhood in which Gropper grew up “was an amazing social laboratory in which, at the expense of thousands of lives, politicians earned their spurs, racketeers learned their professions, and the human organism’s endurance was tested in the face of exploitation, poverty, and disease.”

Young Gropper’s interest in art “began at a young age. As a child of six, he took chalk to the sidewalks, decorating the concrete with elaborate picture stories of cowboys and Indians that extended around the block.” At the age of 13 after graduating from public school, he took his first instruction in art in Harlem at the radical Ferrer School, which had been founded by a group of anarchists that included Alexander Berkman and Emma Goldman. He earned a scholarship to the Parson’s school of fine and applied arts and but continued to work part-time in a clothing store to help support his family.

In 1917, William Gropper joined the staff of the New York Tribune, and for the next four years, he earned a steady income (and a good one — $40/week) doing “tiny” drawings for the paper’s special Sunday feature articles. As a socialist, he mixed with radical cartoonists such as Rockwell Kent, Art Young, Boardman Robinson, and Robert Minor among others, some of whom drew for the left-wing magazine, The Masses. Founded in 1911, The Masses went out of business in 1917 after its editors were tried for treason because of the magazine’s anti-war posture during World War I; neither of two trials reached a guilty verdict.

The Masses was catholic in “its freedom from the one-track mental habit of the rabid devotee of a cause,” Max Eastman, its editor, once wrote, years after the magazine had gone out of business under various legal pressures brought against it.

Eastman continued: “I never could see why people with a zeal for improving life should be indifferent to the living of it. Why cannot one be young-hearted, gay, laughing, audacious, full of animal spirits and yet also use his brains? The everlasting cerebral attitude of such papers as The Nation and The New Republic, the steady, unbillowy, unjoy-disturbed throbbing of grey matter in their pages, makes me, after some months, a little dogsick.

“And yet on the other hand, I hate and always did hate smart-alecky and irresponsible leftism… The basic political trait of The Masses was its emphasis on liberty as the goal of the class struggle… [Among its motivating goals, perhaps the last of them after mostly political ones, was] also the religious motive, the desire of God’s orphans to believe in something beyond reality.”

In his notebook, Eastman reports, he once had written: “I can bear the prospect that the world may never be free, but I cannot bear the prospect of my living in it and not taking part in the fight for freedom.”

In 1918, Eastman established a new magazine, The Liberator, to continue in the same vein as The Masses, and Gropper became a contributor. In January 1921, the year Gropper left the Tribune to freelance, Eastman made him “a special contributor” (akin, I suppose, to “staff member”). Years later, Eastman recorded his first meeting with William Gropper:

“It was one of the brightest mornings in the office when a youth with large blue eyes and the manner of a just-about-to-be-startled fawn stepped in softly with a little sheaf of drawings in ink on tiny squares of paper. They were signed with the funny name of Gropper, and they were funny. Some of them had no captions; others had captions not of themselves jocular, like ‘You’re a Liar!’ or ‘An’ you mean to tell me that that dog ain’t got no fleas!’ But they were all funny. They were his first drawings to be offered for publication [no: Gropper had been cartooning at the Tribune since 1917], and I never felt more definitely in the presence of what is called a budding genius.

“It was one of the brightest mornings in the office when a youth with large blue eyes and the manner of a just-about-to-be-startled fawn stepped in softly with a little sheaf of drawings in ink on tiny squares of paper. They were signed with the funny name of Gropper, and they were funny. Some of them had no captions; others had captions not of themselves jocular, like ‘You’re a Liar!’ or ‘An’ you mean to tell me that that dog ain’t got no fleas!’ But they were all funny. They were his first drawings to be offered for publication [no: Gropper had been cartooning at the Tribune since 1917], and I never felt more definitely in the presence of what is called a budding genius.

“Gropper has gone in for political-party-regulated cartoon wit rather more than is good for him, but I think he still has more humor in his actual drawing than any other American artist since Art Young. At least I would place him side by side in that respect with James Thurber. A sort of liquid humor unhinges the very muscles of these men when they draw. The drawing is funny as well as the things drawn. There may be a witty caption, bit its wit is not so much illustrated as enriched by the picture.

“Gropper [is] as instinctively comic an artist as ever touched pen to paper…”

Increasingly through the years, Eastman edited The Liberator as an editor rather than as the chairman of a co-operative: he changed syntax in articles and captions for cartoons without consulting anyone. When his contributors finally threatened a mutiny, he resigned as editor and went to visit Soviet Russia. Meanwhile, The Liberator became a de facto organ of the Communist Party from late 1922; in 1924, it was renamed The Workers’ Monthly.

GROPPER, who was contributing to other radical magazines (like The Rebel Worker, The Morning Freiheit, and The Revolutionary Age) as well as mainstream magazines (The Bookman, The Dial, and Frank Harris’ New Pearson’s Magazine), married his second wife in 1924, and the two spent a year in Russia, where William Gropper was employed briefly by the All-Union Communist Party’s newspaper, Pravda. In 1927, Gropper toured the Soviet Union with novelists Sinclair Lewis and Theodore Dreiser in recognition of the tenth anniversary of the Russian Revolution.

In 1925, Gropper was hired by the New York World. And in 1926, he joined several alumni of The Masses and The Liberator to found The New Masses, to which he contributed regularly through the 1930s and 1940s. He also began doing book illustration, painting generally and painting murals particularly.

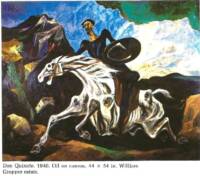

His painting, says Lozowick, “was impressive for the effortlessness with which the artist handled the medium and the obvious pleasure he took in its sensuous quality: in the endlessly rich possibilities of pigment and color, the juxtaposition of related and contrasting tonalities, the transparency of some areas and the textual impasto of others. He seemed to enjoy the very act of laying on color and mixing of one paint with another. As might be expected from an accomplished graphic artist, drawing is the backbone of Gropper’s painting. It provides a scaffolding for the intricate pictorial architecture in which color is an integral part.”

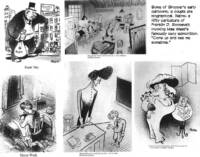

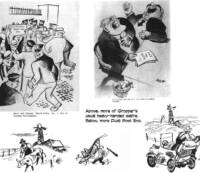

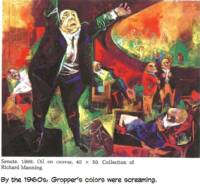

In his cartoons and other illustrations, Gropper reflected a keen sense of social injustice, and during the Great Depression, his work was very influential; he faithfully championed workers as noble but subjugated and exploited laborers while politicians and industrialists were heartless monsters. He attacked the growth of fascism in Germany and Italy, and he was determinedly against anti-Semitism. During World War II, he was increasingly concerned with the growth of the extreme Right in the U.S.

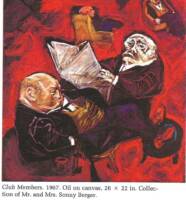

“His best known subject matter is biting caricature of America’s wealthy and powerful, of politicians, moguls of business and industry, yet many of these same types proudly number Gropper work among their private collections,” reports August L. Freundlich in his William Gropper: Retrospective (1968).

His subjects always included grasping politicians but also peasants, American folklore, war, and Jewish village life.

“You don’t paint with color,” Freundlich quotes Gropper as saying, “you paint with conviction, freedom, love and heartaches — with what you have. The other end is the technique, the equipment with which you convey that.”

Time magazine, reporting on a one-man show of Gropper paintings, noted “the most important fact: stocky William Gropper, a punch-packing cartoonist, is a still better painter. He paints as he draws, quickly and simply, without benefit of model, in reds, blues, yellows, whites… [producing] typically class-conscious canvases [of] ‘The Shoemaker,’ who is mending other men’s shoes while barefoot himself; Brenda in a tantrum, which shows 1939’s Glamor Girl No.1 streaming indignantly through the air; and ‘Art Patrons,’ a jut-jawed couple gazing bleakly at a picture they dislike.”

Time continues: “For The Freiheit, Manhattan’s Yiddish Communist paper, Gropper does a daily cartoon, gets paid when The Freiheit can afford it. Without pay, he cheerfully draws for The New Masses, The Sunday Worker. He makes his living freelancing for capitalist publications, from Vogue to Fortune, painting murals for bars, hotels, government buildings. His conservative employers run no risk of embarrassment. ‘To paint a mural that doesn’t fit the place would be like painting swastikas in a synagogue,’ observes Artist Gropper. ‘If I were to paint a proletarian scene in a post office, [Postmaster General] Farley would jump out of his pants. My only interest, where I haven’t got a free hand, is to do as good a job as possible.’”

In spite his contributing regularly to an array of communist publications (and his friendship with John Reed), William Gropper was never formally a member of the American Communist Party. But his attacks on Joseph McCarthy in the 1950s resulted in his being called before the House of Un-American Activities Committee. He refused to answer questions, claiming (correctly) that the Fifth Amendment of the Constitution gave him the right to do so. Although blacklisted, Gropper was never imprisoned like the Hollywood Ten of the same period. (His being blacklisted may be why we haven’t heard about him: the blacklist worked.)

In 1956, a major exhibition of his work was mounted at Piccadilly Gallery in London. The next year, came the Galerie del Frente Nacional des Artes exhibition in Mexico. Gropper’s work was featured in 25 major exhibitions from 1921 to 1972 — in Rome, in Prague, in New York (ACA Galleries), Los Angeles, San Francisco, Miami and elsewhere.

His first one-man show was in 1936. Says Lozowick: “He was already known as one of America’s outstanding cartoonists and caricaturists; now, he took his place with its leading contemporary painters. In this double career, he is unique among the artists in America. Actually, Gropper has never been exclusively a painter or a cartoonist, although he has worked predominantly in one or the other mode at certain points in his career.

“Despite his enormous output of drawings, cartoons, illustrations, and sandpaper print, he managed to steal time for painting, and occasionally for exhibiting. As early as 1921, he had a show of monotypes, and in 1935, he completed a mural, The Wine Festival, for the Schenley Corporation.”

In 1932, Gropper was one of several artists invited to submit to the Museum of Modern Art sketches for murals on themes of their own choice. Gropper’s theme was so critical of the establishment, “particularly of the military-industrial complex, that the trustees could not decide whether to hang it. Nelson Rockerfeller took the matter up with J.P. Morgan.

‘Of course you’ve got to hang it,’ said Morgan. ‘Don’t give it a second thought.’

“The picture was hung. And that was the last Gropper ever saw of it.” It famously disappeared.

His last major work was the production of stained glass windows for Temple Har Zion, River Forest, Illinois (1965-67).

Gropper died from myocardial infarction at Manhasset on January 6, 1977. We close with a short gallery of more of Gropper’s oeuvre and hope that this brief encounter with his work, cartooning and painting and both together, may prompt a revival of interest in the stocky guy with the blue eyes, William Gropper. Just for practice, say his name a few times. Get to know him.

- Funnies Farrago Celebrates a Half Century of Doonesbury - June 1, 2022

- Who Really Invented the Comic Character ‘Archie’? - May 7, 2022

- Dick Wright Returns - April 5, 2022