In the Mythology of the Western, even comedy can be authentic.

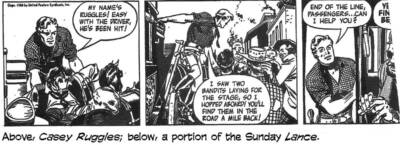

Perhaps the most spectacular of the comic strip Westerns were the two produced by Warren Tufts, Casey Ruggles, Sunday and daily (1949-1954), and Lance, a stunning full-page Sunday (1955-1957). Tufts’ stories were realistic, even brutally so sometimes, but Casey, a freelance lawman wandering the West (mostly California), and Lance, an officer in the U.S. cavalry, wore meticulously pressed duds, freshly laundered every day.

Tufts’ artwork was expert and elegant — Alex Raymond in a broad-brimmed hat but still a fashion plate — and altogether admirable, inspiring a cult-like devotion among afficiandoes of the medium, but it was too much Hollywood and not enough cookfire smoke and wood ash.

Tufts’ artwork was expert and elegant — Alex Raymond in a broad-brimmed hat but still a fashion plate — and altogether admirable, inspiring a cult-like devotion among afficiandoes of the medium, but it was too much Hollywood and not enough cookfire smoke and wood ash.

For authenticity, I preferred Bailin’ Wire Bill — an unknown, I’m sure, if ever one wandered in off the prairie, scuffing the cow-pie off’n his boots as he crossed the front stoop and smilin’ a shy smile. Unless you grew up in the so-called “Rocky Mountain Empire” as proclaimed and defined by the Denver Post, you probably never heard of Balin’ Wire Bill. So, let me change that forever. Return with me to the days of yesteryear. Out of the past come the hoofbeats of the cow pony Kate.

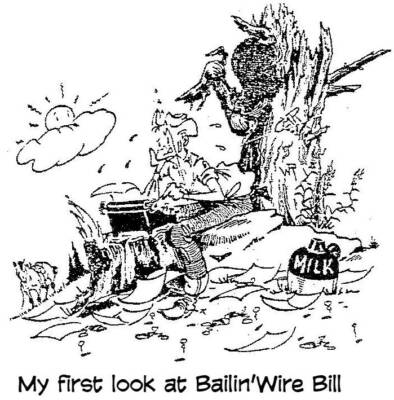

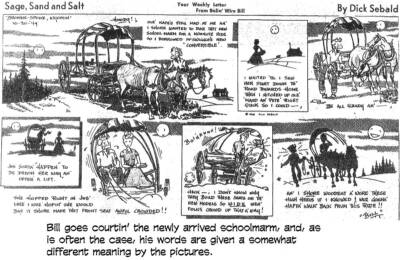

Somewhere in this vicinity is the first drawing I ever saw of Balin’ Wire Bill. I clipped the drawing but neglected to clip the news story that accompanied it. Now, yellowed with age, it still conjures up fond memories for me of a year spent waiting for Bill’s weekly appearances. But without the text that doubtless ran with this faded clipping, I can tell you nothing about Dick Sebald, the man who produced the comic strip that was the favorite of my youth.

The drawing speaks volumes, though, of its artist’s graphic invention, his playfulness. Notice how the line that makes Bill’s eyebrow gets carried away with itself and becomes a string somehow attached to his wrist as he types. Notice the cigarette butts strewn around, signifying that Bill has been agonizing over his composition. Notice the texture of the aged tree trunk and the initials carved thereon. “CMR” is Charles M. Russell, the great cowboy painter we met in Part One of this series, and “WR” is doubtless another former wrangler, Will Rogers, one of this country’s fabled folksy heroes and humorists. Also, at first, a cowboy.

The drawing speaks volumes, though, of its artist’s graphic invention, his playfulness. Notice how the line that makes Bill’s eyebrow gets carried away with itself and becomes a string somehow attached to his wrist as he types. Notice the cigarette butts strewn around, signifying that Bill has been agonizing over his composition. Notice the texture of the aged tree trunk and the initials carved thereon. “CMR” is Charles M. Russell, the great cowboy painter we met in Part One of this series, and “WR” is doubtless another former wrangler, Will Rogers, one of this country’s fabled folksy heroes and humorists. Also, at first, a cowboy.

Rogers got started as a humorist when he began to talk as he did his rope tricks on the vaudeville stage; pretty soon, the talk got so interesting that he forgot about doing rope tricks. He never met a man he didn’t like, Rogers said. He also said that all he knew was what he read in the newspapers. And he specialized in political commentary of a mildly bemused sort. “Every time we have an election,” he said, “we get in worse men and the country keeps right on going. Times have proven only one thing and that is you can’t ruin this country ever, with politics.” And: “Common sense is not an issue in politics; it’s an affliction.”

I’m not so sure, any more, that we can’t ruin the country with the inferior caliber of the politicians we elect; but Rogers’ notion of common sense in politics is still undeniably true.

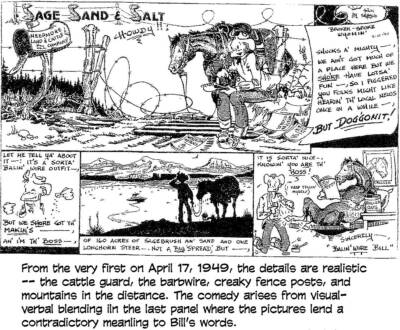

Sebald was clearly evoking the right gods in this drawing — the gods of authenticity and humor that he hoped would smile upon his creation, just about to be launched. Whimsically entitled Sage, Sand, and Salt, the strip had humor as its object — not western action or, even, much adventure. In the strip, the contemporary West of the late 1940s found its voice in a weekly “letter” from Balin’ Wire Bill. The letter was Sebald’s strip. It ran in Sunday format, several black-and-white panels on two tiers in the Denver Post’s Sunday magazine supplement, Empire.

Its humor wasn’t biting satire; it was folksy. And the artwork wasn’t particularly spectacular — although it had a homespun charm, capturing the fustian atmosphere of a one-horse ranch in the modern arid West. But the reason that few are likely to recall this strip is that it ran for less than a year in 1949, exclusively in Empire. Appearing in a magazine that used halftones permitted cartoonist Sebald to embellish his work with a wash, which he did more and more towards the end of the strip’s run. And very effectively, too.

I was a passionate fan of Sebald’s in those days — and I copied his drawings slavishly. I learned how to draw horses by copying “ol’ Kate.” Sebald drew cartoon horses as well as Russell drew real ones. And he also authoritatively evoked the ambiance of the country — the rocks and trees and shrubs and the fence posts and tangled barbed wire. And the mountains. Not to mention Levis and boots and saddles. I copied it all. I drew a character that was Balin’ Wire Bill’s spitin’ image for a year or more, decorating my school books and homework papers with pictures of him.

Bill had nice, friendly sorts of adventures. Beginning April 10, 1949, the introductory sequence acquainted us with Bill’s ranch and its population — namely, Kate, his horse (hopelessly enamored of Roy Rogers’ Trigger), and Tex, the resident obligatory longhorn steer.

Bill had nice, friendly sorts of adventures. Beginning April 10, 1949, the introductory sequence acquainted us with Bill’s ranch and its population — namely, Kate, his horse (hopelessly enamored of Roy Rogers’ Trigger), and Tex, the resident obligatory longhorn steer.

In the first “story,” Bill tries to put his own brand on Tex, who is already copiously branded, his hide covered in burned-on marks. No luck. Noticing Bill heating up a branding iron, the savage longhorn charges after him and trees him, and while up in the tree, Bill tells us how Tex got all those brands all over his body: he did it himself, plugging one of his horns into an electrical socket, and then using the other end, now charged and hot as a branding iron, to draw the brands all over himself. That way, the steer reasoned, no one could claim him, and he’d be able to run free over the range. Preposterous.

Bill gets out of the tree by singing “Deep in the Heart of Texas,” a particular favorite of Tex’s, who, overcome by the sentiment of the moment, lets Bill climb down and resume his ordinary life on the ranch.

Bill gets out of the tree by singing “Deep in the Heart of Texas,” a particular favorite of Tex’s, who, overcome by the sentiment of the moment, lets Bill climb down and resume his ordinary life on the ranch.

In other adventures, Bill goes to the famous Cheyenne Frontier Days in July. He buys himself a fancy cowboy suit for the occasion, but Kate is so frightened by the Hollywood outfit that she runs off, so Bill hangs it in the closet and dons his customary jeans. He enters the calf-roping contest, but he’s so inept a cowboy that when he ropes a calf, he ties himself up with the piggin’ string, not the animal. A pretty young woman shows up as the school marm one week, and Bill is smitten. Well, you get the idea.

My last clipped strip is dated December 11, 1949, and I think that might, indeed, be the last date it ran. It was a short but inspiring run. All make-believe, of course, but, like all Western mythology, not fraudulent at all.

My last clipped strip is dated December 11, 1949, and I think that might, indeed, be the last date it ran. It was a short but inspiring run. All make-believe, of course, but, like all Western mythology, not fraudulent at all.

Read the Mythology of the Western, Parts One and Two!

- Funnies Farrago Celebrates a Half Century of Doonesbury - June 1, 2022

- Who Really Invented the Comic Character ‘Archie’? - May 7, 2022

- Dick Wright Returns - April 5, 2022