Edward Gorey could make us shiver as we grinned and vice versa (mostly vice).

Author and artist, ballet enthusiast nonpareil, cat lover extraordinaire and master of the spectacularly unassuming macabre, Edward St. John Gorey (22 February 1925 – 15 April 2000) was born ordinarily enough in Chicago, Illinois, the son of Edward Leo Gorey, a newspaperman, and Helen Dunham (Garvey) Gorey, a government clerk. They were not ordinary parents: they divorced when their son was eleven and remarried when he was twenty-seven.

Other strangenesses emerged. By the age of three, young Edward had taught himself to read, revealing the precocity that would enable him to skip both first and fifth grades in elementary school. By the time he was five, he had read Dracula and Alice in Wonderland. These works, so profoundly different in both substance and manner, would have a lasting effect upon his artistic sensibility.

Other strangenesses emerged. By the age of three, young Edward had taught himself to read, revealing the precocity that would enable him to skip both first and fifth grades in elementary school. By the time he was five, he had read Dracula and Alice in Wonderland. These works, so profoundly different in both substance and manner, would have a lasting effect upon his artistic sensibility.

At nine, he read Rover Boys books while at summer camp and formed a lifelong admiration for the series. He attended the progressive Francis W. Parker high school, and after graduating, he studied at the Chicago Art Institute for a semester before being inducted into the U.S. Army in 1943. He spent the rest of World War II stationed at Dugway Proving Ground, Utah, testing site for mortars and poison gas, where he served as a company clerk.

Upon discharge in 1946, Edward Gorey entered Harvard College. There, he majored in French, acquiring an enduring interest in French Surrealism and Symbolism as well as Chinese and Japanese literature.

Graduating in 1950, Gorey worked in Boston bookstores part-time, tried to write novels (none of which he ever finished), and “starved, more or less,” as he put it (“my family was helping to support me”), until meeting editor and publisher Jason Epstein, who was starting a new division at Doubleday, Anchor Books, to produce trade paperback versions of out-of-print classics.

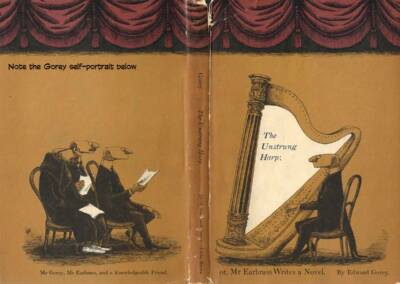

Gorey drew many of the covers for the early Anchor editions, and when offered a job in the art department, he moved to Manhattan in 1953. He took an apartment in a nineteenth century townhouse at 36 East 38th Street and, staying late at the office, began work on his first book, The Unstrung Harp. Published later in the year, this slender volume depicts (in prose on one page facing an illustration on the next) the impermeably mundane life of a professional writer, who begins a new novel every other year on 18 November exactly.

Gorey drew many of the covers for the early Anchor editions, and when offered a job in the art department, he moved to Manhattan in 1953. He took an apartment in a nineteenth century townhouse at 36 East 38th Street and, staying late at the office, began work on his first book, The Unstrung Harp. Published later in the year, this slender volume depicts (in prose on one page facing an illustration on the next) the impermeably mundane life of a professional writer, who begins a new novel every other year on 18 November exactly.

Gorey also met Frances Steloff, founder of the Gotham Book Mart and champion of such unconventional authors as James Joyce; she became one of the first to carry his books.

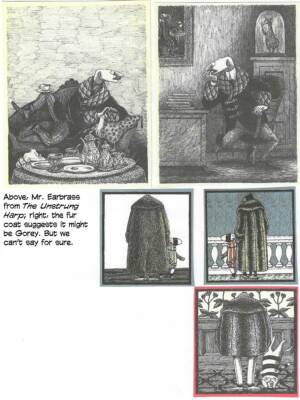

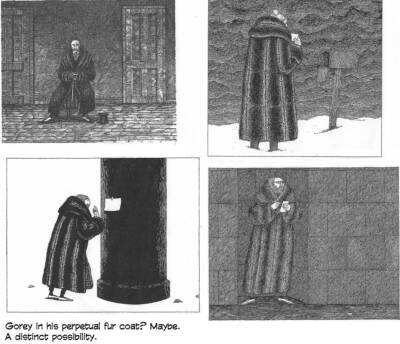

In 1957, Gorey began attending performances of the New York City Ballet. Enamored of the choreography of George Balanchine, Gorey achieved perfect attendance for twenty-five years, unfailingly attired in a floor-length fur coat, long scarf, blue jeans, and white sneakers, which, in combination with his full-bearded visage, created an appearance “half bongo-drum beatnik, half fin-de-siecle dandy” according to Stephen Schiff, writing in The New Yorker in 1992.

By 1959, four of his books had been published and had attracted the attention of critic Edmund Wilson, who provided the first important notice in a review in The New Yorker, calling Gorey’s work “surrealistic and macabre, amusing and somber, nostalgic and claustrophobic, poetic and poisoned.”

By 1959, four of his books had been published and had attracted the attention of critic Edmund Wilson, who provided the first important notice in a review in The New Yorker, calling Gorey’s work “surrealistic and macabre, amusing and somber, nostalgic and claustrophobic, poetic and poisoned.”

The same year, Gorey, with Epstein and Clelia Carroll, founded and worked for Looking Glass Library, a division of Random House that published classical children’s books in hardcover; Wilson was one of the consulting editors (as were W.H. Auden and Phyllis McGinley).

In 1961, Gorey illustrated The Man Who Sang the Sillies, the first of a half-dozen of John Ciardi’s works that he would illuminate, and he employed the first of his numerous pen-names (all anagrams of his name) in The Curious Sofa by Ogdred Weary. He launched the Fantod Press in 1962 to publish those of his works that failed to enlist support elsewhere. A year later, Looking Glass Library collapsed, and Gorey, with fourteen of his books published, went to work for Bobbs Merrill.

After an unsatisfactory year, he quit the job and the workaday world; henceforth, he would earn a living solely as a freelance author and illustrator, eventually producing over ninety of his own works and illustrating another sixty by others (Edward Lear and Samuel Beckett among them).

IN 1967, STELOFF SOLD THE GOTHAM BOOK MART to Andreas Brown, who entered into an unusual relationship with Gorey: in 1970, Gorey’s The Sopping Thursday became the first of his books to be published by the bookstore, which also mounted an exhibition of his works that year and began serving as an archive for his art. Gorey’s 1972 anthology reprinting the first fifteen of his books, Amphigorey, won an American Institute of Graphic Arts award as one of the year’s fifty best-designed books.

In 1964, Gorey began spending more and more time at Cape Cod, where he became involved in theatrical enterprises, reviving his earlier interest in the field. He designed sets and costumes for the Nantucket summer theater production of Dracula in 1973 and again in 1977 for the Broadway production, winning a Tony Award for costume design.

All of Gorey’s subsequent theatrical works were produced on or near Cape Cod, where he died at the hospital in Hyannis after suffering a heart attack three days earlier.

Gorey’s oeuvre reached television in 1980 when he designed the first version of the swooning lady animated titles for Public Broadcasting System’s Mystery!

Upon the death of Balanchine in 1983, Gorey moved permanently to Cape Cod, first to Barnstable and then to Yarmouthport, remaining there for the rest of his life and setting another perfect attendance record—this time, at a local diner named Jack’s Outback, where he ate breakfast and lunch every day.

By the time of his death, Gorey had become a local institution. Jack Braginton-Smith, owner of Jack’s Outback, was Gorey’s friend and admirer and curator of his memory and memorabilia.

“He was very fast and he was constantly doing things gratis for anyone who needed visual work,” Braginton-Smith told a reporter. “I don’t think there’s a theatrical group or a literary group or a musical group on Cape Cod that he hasn’t done a poster or something for at no charge.”

His restaurant is a museum of Goreyana. And much of it is, understandably, typical Gorey.

Gorey’s 200-year-old house at 8 Strawberry Lane in Yarmouthport was built by a sea captain, Nathaniel Howes. A conventional two-story structure originally, it was modified by extensive alterations in Victorian times and gradually assumed a distinctive aspect all its own. Its walls were festooned with bookshelves, which were jammed with books, videotapes, CDS, and cassettes; and the floors were littered with stacks of the same as well as finials of all description, occasional lobster floats, cat-clawed furniture, an old toilet with a tabletop, and a small commune of cats. The artwork on the walls ranged from Berthe Morisot to George Herriman, early twentieth century modernists to newspaper cartoonists.

A compulsive collector and consumer of every aspect of the culture in which he was immersed, Gorey was a man of enormous erudition whose tastes and interests ranged from cultivated esoterica to trashy television, all passionately studied in an effort, he told Schiff, to “keep real life at bay.”

IN HER BOOK ABOUT GOREY, Karen Wilkin asserted that “he appears to have read everything and to have equal enthusiasm for classic Japanese novels, British satire, television reruns, animated cartoons, and movies both past and present, good and not so good.”

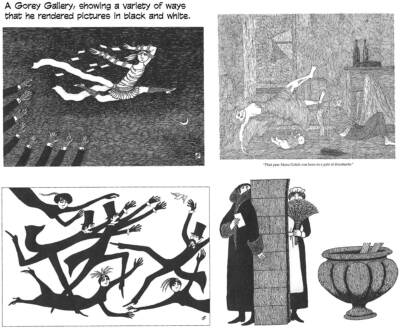

Except for four out-sized anthologies, his books are all small in dimension and liberally illustrated (usually a picture on every other page) in the manner of children’s books. But the humor in his tales can be properly grasped only by adults who can savor the hilarity created by the unexpected juxtaposition of Gorey’s somber albeit caricatural renderings and his deadpan prose. The world he evoked is ostensibly a genteel one, an elegant past now gone to seed, usually populated by bored crypto-Edwardians, whom he depicts with spindly figures and spherical or egg-shaped heads.

The pictures in some of his books are as unembellished as Japanese prints, but Gorey’s characteristic manner is to garnish his drawings with meticulous hachuring and pointillist cross-hatching, so intensely applied as to be almost painful in its exquisite punctiliousness. (“It’s partly insecurity,” he once explained: “I mean, where do you leave off?”) This technique plunges his fictional milieu into deep fustian shadow, giving the stories a vaguely sinister, melancholy menace.

The pictures in some of his books are as unembellished as Japanese prints, but Gorey’s characteristic manner is to garnish his drawings with meticulous hachuring and pointillist cross-hatching, so intensely applied as to be almost painful in its exquisite punctiliousness. (“It’s partly insecurity,” he once explained: “I mean, where do you leave off?”) This technique plunges his fictional milieu into deep fustian shadow, giving the stories a vaguely sinister, melancholy menace.

Contributing to the ambiance is Gorey’s parallel text of hand-lettered laconic declarative sentences (sometimes in rhyme) that relate the most disturbing events in an almost elliptical fashion. In The Loathesome Couple (1977), the titular pair kidnap a young girl and spend the better part of a night “murdering the child in various ways.” The Curious Sofa (subtitled “A Pornographic Work”) includes the immortal line, “Still later Gerald did a terrible thing to Elsie with a saucepan.”

In The Admonitory Hippopotamus (unpublished at the time of Gorey’s death), five-year-old Angelica playing in a gazebo suddenly sees a spectral hippopotamus “rising from the ha-ha.” “Fly at once,” commands the hippo; “all is discovered.”

Gorey left this narrative without illustrations. Drawing a ha-ha was perhaps too much of a challenge.

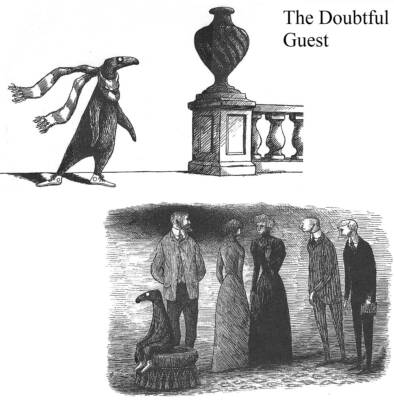

THROUGHOUT HIS OEUVRE, ghastly events are described in a bland, unemotional style “as though the narrator hadn’t quite grasped the gravity of the situation,” as Schiff put it. As disasters overtake them, the principals themselves seem as oblivious as the indifferent gods. The Doubtful Guest (1958) is vintage Gorey. In it, a furry sort of penguin, wearing a long scarf and tennis shoes, shows up uninvited at a dreary mansion and, without the slightest resistance from the resident Edwardian family, makes itself at home, peering up flues in fireplaces, tearing up books, sleepwalking, dropping favorite objects into the pond, and eating the china for breakfast.

“Every Sunday it brooded and lay on the floor, / Inconveniently close to the drawing-room door” where its prone form blocks entrance and egress. Nothing is ever resolved; day after day, the household watches the creature numbly until at last the narrative concludes inconclusively: “It came seventeen years ago—and to this day / It has shown no intention of going away.”

“Every Sunday it brooded and lay on the floor, / Inconveniently close to the drawing-room door” where its prone form blocks entrance and egress. Nothing is ever resolved; day after day, the household watches the creature numbly until at last the narrative concludes inconclusively: “It came seventeen years ago—and to this day / It has shown no intention of going away.”

Incidentally, Arcane Vault has produced an excellent Doubtful Guest pinch button that is sold at Amazon for about ten bucks, a reasonable price for a Gorey artifact; search Arcane Vault Edward Gorey Doubtful Guest Pinch Button.

Gorey cautioned against taking his work seriously: it would be “the height of folly,” he said.

Still, when a publisher rejected one of his books on the grounds that it wasn’t funny, Gorey professed astonishment: “It wasn’t supposed to be,” he said; “what a peculiar reaction.”

Mel Gussow, writing The New York Times obituary, delivered perhaps the best assessment: “He was one of the most aptly named figures in American art and literature. In creating a large body of small work, he made an indelible imprint on noir fiction and on the psyche of his admirers.”

Soon after Gorey died, Braginton-Smith launched an effort to create a memorial to Gorey. He proposed that they install and cultivate on the village green a topiary sculpture of a Gorey creature (perhaps the splendidly mysterious Doubtful Guest?).

“My purpose is to make sure Edward Gorey remains a figure in our history,” said Braginton-Smith.

It certainly seems like a good idea. A Gorey of an idea. But let me give the last word to the artist himself. “You know, Ted Shawn, the choreographer,” Gorey mused in Schiff’s hearing, “—he used to say, ‘When in doubt, twirl.’ Oh, I do think that’s such a great line.”

It certainly seems like a good idea. A Gorey of an idea. But let me give the last word to the artist himself. “You know, Ted Shawn, the choreographer,” Gorey mused in Schiff’s hearing, “—he used to say, ‘When in doubt, twirl.’ Oh, I do think that’s such a great line.”

Indeed.

Footnote: The two best sources of information about Gorey’s life and work are Stephen Schiff, “Edward Gorey and the Tao of Nonsense,” The New Yorker, 9 November 1992, and Clifford Ross and Karen Wilkin, The World of Edward Gorey (1996), containing samples of his drawings, an interview, an extensive critical examination, and a chronology and complete bibliography. Four anthologies collect over eighty of Gorey’s books: Amphigorey (1972), Amphigorey Too (1975), Amphigorey Also (1983), and the posthumous Amphigorey Again (2006).

An obituary is in The New York Times, 17 April 2000, and a useful remembrance is Alison Lurie (to whom The Doubtful Guest is dedicated), “On Edward Gorey,” The New York Review, 25 May 2000. A longer, more inclusive bibliography can be found at RCHarvey.com in Harv’s Hindsight for September 5, 2001.

- Funnies Farrago Celebrates a Half Century of Doonesbury - June 1, 2022

- Who Really Invented the Comic Character ‘Archie’? - May 7, 2022

- Dick Wright Returns - April 5, 2022